PFNA Accelerates Weight-Bearing and Lowers Cut-Out Rates versus DHS in AO/OTA 31A2-A3 Fractures

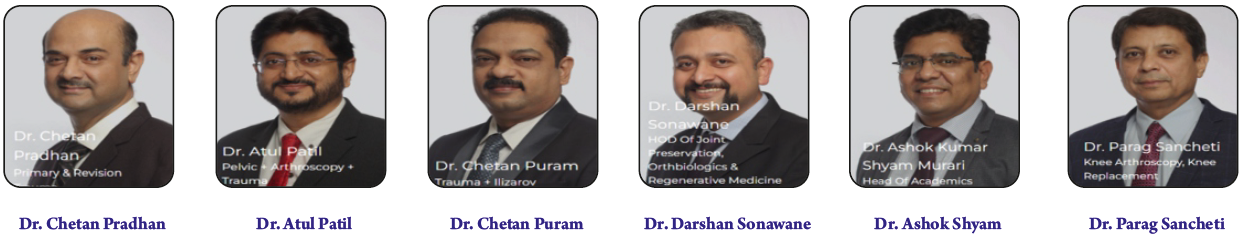

Vol 8 | Issue 1 | January-June 2022 | page: 17-20 | Meghraj Holambe, Chetan Pradhan, Atul Patil, Chetan Puram, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam, Parag Sancheti

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i01.178

Author: Meghraj Holambe [1], Chetan Pradhan [1], Atul Patil [1], Chetan Puram [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1], Parag Sancheti [1]

[1] Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Email : researchsior@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background: Fractures of the extracapsular proximal femur are common in older people and can change the course of life. They bring pain, loss of mobility and a high risk of medical complications unless the hip is stabilized promptly. Cephalomedullary nailing offers a load-sharing, intramedullary option that works well when the medial calcar or lateral wall is deficient. Careful implant choice and precise surgical technique help patients begin walking sooner and reduce harms of prolonged bedrest.

Hypothesis: For unstable extracapsular fractures (AO/OTA 31-A2 and 31-A3), cephalomedullary nailing will provide stable fixation that supports early weight bearing and leads to radiographic union and functional recovery when reduction and implant placement are optimized. Selecting nail length to suit femoral shape and choosing proximal fixation (helical blade versus lag screw) for bone quality will influence complication risk, but these measures are effective only when reduction and positioning are correct.

Clinical importance: Choosing the right implant and applying it with sound technique can be decisive for whether a patient returns home or requires long-term care. Early mobilisation after stable fixation truly lowers the risks of pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, pressure injuries and loss of independence. Multidisciplinary perioperative care — geriatric assessment, focused rehabilitation, nutrition and fall prevention — magnifies the benefit of stable fixation and raises the chance of regaining prior function. Clear communication with patients and families supports realistic expectations and shared decisions.

Future research: Future studies should compare fixation strategies within well-defined fracture subtypes, include frailty measures and patient-reported outcomes, and evaluate augmentation methods for severely osteoporotic bone. Large registries and multicentre trials can detect uncommon device-specific complications and help tailor fixation to patient anatomy, physiology and goals. Research should prioritise outcomes that matter to patients, such as return to independent living.

Keywords: Extracapsular hip fracture, Cephalomedullary nail, Intertrochanteric fracture, Helical blade, Early mobilisation

Background:

Fractures around the trochanteric region of the femur are common and growing in number as populations age; they cause long hospital stays, loss of independence and a significant rise in mortality during the year after injury [1]. The AO/OTA classification is widely used to separate stable from unstable extracapsular patterns and helps guide treatment decisions [2]. Unstable patterns — those with posteromedial comminution, loss of the medial calcar, breach of the lateral wall or reverse-obliquity geometry — behave differently from simple intertrochanteric fractures and are especially prone to varus collapse and fixation failure unless the mechanical problem is addressed [3]. Systematic reviews and pooled analyses of randomized trials have explored intramedullary versus extra medullary fixation; while there is no single implant that dominates for every fracture type, evidence suggests intramedullary nails have biomechanical advantages for many unstable configurations [4].

The surgical treatment of proximal femur fractures has evolved over more than a century, with early descriptions and classic texts laying the conceptual groundwork for modern fixation strategies [5]. Cephalomedullary nails (CMN) were developed to shorten the bending moment on the proximal fragment, permit closed reduction with less soft-tissue disruption, and support earlier weight bearing — qualities that suit frail, osteoporotic patients [6]. Implant designs diversified rapidly: short versus long nails, lag-screw versus helical-blade proximal fixation, single versus dual proximal screws — each variant aiming to improve purchase in weak cancellous bone, reduce particular failure modes, or simplify insertion [7].

Finite-element and biomechanical work support the mechanical rationale for intramedullary constructs: by moving the load closer to the shaft’s neutral axis they reduce bending moments and better resist varus collapse in unstable fractures [8]. Clinical comparisons, including series focused on reverse-obliquity or subtrochanteric extension, suggest specific nails perform more reliably in defined settings [9]. Large randomized trials and meta-analyses add nuance: for many simple, stable intertrochanteric fractures sliding hip screws and CMN produce similar outcomes when reduction and technique are good, but CMN often show advantage in unstable patterns [10].

Practical trade-offs matter. Short nails reduce operative time and blood loss and are appropriate for many trochanteric fractures, while long nails distribute stress more distally and can reduce the risk of peri-implant shaft fracture in femora with marked bowing or when the fracture extends distally; systematic reviews and comparative trials have documented broadly similar functional outcomes but different complication profiles and resource use [11–14]. Cost and complication analyses also inform implant choice in real-world settings [15, 16].

Technical execution remains the most important determinant of mechanical success. Central placement of the proximal device, a low tip–apex distance, correct entry point and avoidance of residual varus repeatedly predict reduced cut-out and loss of reduction. Device-specific complications (for example, blade migration or Z-effect phenomena) are uncommon when technique is sound but remain important to recognise [17–19]. Decision making between sliding hip screw and CMN should be guided by fracture mechanics; for stable patterns a sliding hip screw remains reasonable in many hands, while CMN are often preferable for unstable fractures with medial or lateral wall compromise [20].

Finally, mechanical fixation alone does not determine recovery. Early mobilisation, geriatric co-management, thromboprophylaxis, nutrition and well-structured rehabilitation are essential to convert stable fixation into regained function and independence. Series reporting excellent radiographic union but poor functional outcomes commonly reveal gaps in perioperative care or severe baseline frailty in their populations [21]. The development of intramedullary implants and the evolution of fixation techniques reflect both historical lessons and ongoing efforts to reduce complications and improve patient function [22–25].

Hypothesis

Primary hypothesis: In unstable extracapsular proximal femur fractures (AO/OTA 31-A2 and 31-A3), cephalomedullary nailing provides a stable, load-sharing construct that allows early weight bearing and results in high rates of radiographic union and meaningful functional recovery when reduction and implant positioning are optimised [12].

Rationale. The intramedullary location of a CMN brings the load path closer to the femoral neutral axis, lowering bending forces on the proximal fragment and improving resistance to varus collapse when medial support is deficient. When anatomic or acceptable reduction is achieved and the proximal fixation (lag screw or helical blade) is centred with an appropriate depth, the construct tolerates axial loading and supports early mobilisation — a desirable outcome in elderly patients at high risk from prolonged immobility [8, 13].

Secondary hypotheses:

1. Nail length trade-offs. Short nails reduce operative time and soft-tissue insult and suit many fractures confined to the trochanteric region; long nails distribute load farther along the diaphysis and likely reduce peri-implant shaft fracture risk in femora with pronounced bowing or when the fracture extends into the subtrochanteric region. When nail length is chosen with careful attention to femoral anatomy, overall functional outcomes will be similar, although complication patterns will differ modestly by implant length [14, 15].

2. Proximal fixation design. Helical-blade designs may improve purchase in severely osteoporotic femoral heads by compacting cancellous bone and thus lowering rotational instability and cut-out risk when correctly positioned. Properly placed lag screws remain effective in many scenarios [18, 19].

3. Predictors beyond implant. Patient factors — advanced age, frailty, cognitive impairment and multiple comorbidities — and fracture features — severe posteromedial comminution, lateral-wall breach, reverse obliquity — will predict worse function and higher complication rates regardless of implant type. Implant choice cannot fully compensate for poor biology, inadequate reduction, or insufficient perioperative support [3, 16, 20].

These hypotheses reflect clinical pragmatism: randomized evidence has not declared a universal champion across all extracapsular fractures, so the best outcomes come from matching implant design to fracture mechanics, executing sound surgical technique, and providing comprehensive perioperative care [10, 11, 21].

Discussion

The clinical and research literature, together with experience from the attached thesis, point to practical, actionable conclusions. Cephalomedullary nailing is especially suitable for unstable extracapsular fractures where medial or lateral buttress is compromised; the intramedullary position reduces bending moments and helps prevent varus collapse, translating into more predictable mechanical stability in many unstable patterns [18].

Implant selection must be individualized. Short nails are attractive for shorter operative times and smaller operative insult, but in femora with marked anterior bowing or where fracture lines extend distally, a short nail can concentrate stress at its tip and increase peri-implant fracture risk; in those situations a long nail distributes stress and is preferable. Systematic reviews and comparative studies support the idea that functional outcomes are broadly similar overall, but complication profiles differ with nail length and femoral anatomy [11–15].

Proximal fixation geometry influences performance within the constraints of sound reduction and placement. Helical blades aim to improve hold in poor cancellous bone by compaction; they work well when centred and at the correct depth but will fail if positioned eccentrically or if reduction is poor. Lag screws remain dependable when they are placed optimally. The technical variables that consistently predict success — central positioning, acceptable tip–apex distance, restoration of neck–shaft relationship and avoidance of residual varus — are the surgeon’s most powerful tools for preventing mechanical failure [17–19].

Beyond mechanics sit the patient’s medical and functional state. Frailty, multimorbidity and impaired cognition strongly influence recovery. Even the most stable construct will not return a patient to independent ambulation if rehabilitation is inadequate or medical issues are untreated. Best outcomes arise from a systems approach that combines careful orthopaedic technique with early mobilisation protocols, geriatric co-management and nutritional support [21].

Device evolution reflects cumulative learning: historical works chart the long trajectory of fracture care, modern implants build on biomechanical insight, and cohort studies and randomized trials together refine indications. Nevertheless, no device can replace good judgment: implant choice must be balanced against the patient’s goals, physiology and fracture mechanics [22–25].

Limitations in cohort evidence include selection bias, surgeon preference in implant choice, variable follow-up and confounding by comorbidity. Despite these limits, consistent patterns support the practical guidance: for stable AO A1 fractures a sliding hip screw remains a reasonable option; for unstable AO A2/A3 fractures with calcar or lateral-wall compromise, cephalomedullary nailing usually provides more predictable mechanical stability and facilitates earlier rehabilitation [4, 20].

Clinical importance

For practising surgeons the message is direct. Cephalomedullary nailing is a reliable strategy for unstable extracapsular proximal femur fractures when nail length and proximal fixation design are chosen to match fracture mechanics and femoral anatomy. Meticulous reduction, correct entry point and central placement of the proximal device with an appropriate tip–apex distance minimise mechanical complications. At the same time, coordinated perioperative measures — early mobilisation, geriatric input, and thromboprophylaxis and focused rehabilitation — are essential to translate mechanical success into regained function and independence. Thoughtful preoperative planning, careful surgical technique and integrated medical care together improve patient safety and outcome [21, 22].

Future direction

Future studies should prioritise prospective, stratified trials that compare fixation strategies within precisely defined fracture subtypes, explicitly documenting lateral-wall and calcar status. Trials should include frailty indices, standardised patient-reported outcomes, and cost–utility analyses. Multicentre registries are needed to capture uncommon device-specific complications and to inform iterative design improvements. Research into augmentation techniques for severely osteoporotic bone and decision algorithms that integrate patient goals, anatomy and physiological reserve will further personalise care and improve meaningful recovery [14, 15, 16].

References

1. Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1997; 7(5):407–13.

2. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium—2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, OTA. J Orthop Trauma. 2007; 21(10 Suppl):S1–133.

3. Penzkofer J, Mendel T, Bauer C, Brehme K. Treatment results of pertrochanteric and subtrochanteric femoral fractures: a retrospective comparison of PFN and PFNA. Unfallchirurg. 2009; 112(8):699–705.

4. Queally JM, Harris E, Handoll HH, Parker MJ. Intramedullary nails for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 ;( 9):CD004961.

5. Ashhurst AP. Fractures through the trochanter of the femur. Ann Surg. 1913:494–509.

6. Gary JL, Taksali S, Reinert CM, Starr AJ. Ipsilateral femoral shaft and neck fractures: are cephalomedullary nails appropriate? J Surg Orthop Adv. 2011; 20(2):122–5.

7. Bali K, Gahlot N, Aggarwal S, Goni V. Cephalomedullary fixation for femoral neck/intertrochanteric and ipsilateral shaft fractures: surgical tips and pitfalls. Chin J Traumatol. 2013; 16(1):40–5.

8. Yuan GX, Shen YH, Chen B, Zhang WB. Biomechanical comparison of internal fixations in osteoporotic intertrochanteric fracture: a finite element analysis. Saudi Med J. 2012; 33(7):732–9.

9. Min WK, Kim SY, Kim TK, et al. Proximal femoral nail for the treatment of reverse obliquity intertrochanteric fractures compared with gamma nail. J Trauma. 2007; 63(5):1054–60.

10. Parker MJ, Handoll HH. Intramedullary nails for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 ;( 3):CD004961.

11. Hou Z, Bowen TR, Irgit KS, et al. Treatment of pertrochanteric fractures (OTA 31-A1 and A2): long versus short cephalomedullary nailing. J Orthop Trauma. 2013; 27(6):318–24.

12. Tyllianakis M, et al. Treatment of extracapsular hip fractures with the proximal femoral nail (PFN): long term results in 45 patients. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004; 70:444–54.

13. Berger-Groch J, Rupprecht M, Schoepper S, Schroeder M, Rueger JM, Hoffmann M. Five-year outcome analysis of intertrochanteric femur fractures: a prospective randomized trial comparing a two-screw and a single-screw cephalomedullary nail. J Orthop Trauma. 2016.

14. Dunn J, Kusnezov N, Bader J, et al. Long versus short cephalomedullary nail for trochanteric femur fractures (OTA 31-A1, A2 and A3): a systematic review. J Orthop Traumatol. 2016; 17(2):1–9.

15. Krigbaum H, Takemoto S, Kim HT, Kuo AC. Costs and complications of short versus long cephalomedullary nailing of OTA 31-A2 proximal femur fractures in U.S. veterans. J Orthop Trauma. 2016; 30(3):125–9.

16. Vaughn J, Cohen E, Vopat BG, Kane P, Abbood E, Born C. Complications of short versus long cephalomedullary nail for intertrochanteric femur fractures, minimum 1-year follow-up. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015; 25(4):665–70.

17. Parker MJ, Palmer CR. A new hip score for the assessment of outcome after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993; 75(2):261–3.

18. Strauss E, Frank J, Lee J, Kummer FJ, Tejwani N. Helical blade versus sliding hip screw for treatment of unstable intertrochanteric hip fractures: a biomechanical evaluation. Injury. 2006; 37(10):987–9.

19. Min WK, et al. (additional biomechanical and clinical comparisons of implant designs). J Orthop Res. 2008; 26(7):981–7.

20. Joshua Jacob, Ankit Desai, Alex Trompeter. Decision making in the management of extracapsular fractures of the proximal femur – is the dynamic hip screw the prevailing gold standard? Open Orthop J. 2017; 11(Suppl-7):1213–17.

21. Robinson CM, Patel AD, Murray IR. The management of proximal femoral fractures in older patients. Bone Joint J. 2016; 98-B (10):1331–8.

22. Ruecker AH, Rupprecht M, Gruber M, et al. The treatment of intertrochanteric fractures: results using an intramedullary nail with integrated cephalocervical screws and linear compression. J Orthop Trauma. 2009; 23(1):22–30.

23. Cooper A. A treatise on dislocations and on fractures of the joints. 1822.

24. Von Langenbeck B. Verhandl D Deutsh. 1878.

25. Willkie DPD. The treatment of fractures of neck of femur. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1927; 44:529–30.

| How to Cite this Article: Holambe M, Pradhan C, Patil A, Puram C, Sonawane D, Shyam A, Sancheti P. PFNA Accelerates Weight-Bearing and Lowers Cut-Out Rates versus DHS in AO/OTA 31A2-A3 Fractures. Journal of Medical Thesis | 2025 January-June; 08(1):17-20. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS), Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2019

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF