Category Archives: Vol 8 | Issue 2 | July-December 2022

Restoring ≥80% of the Native Tibial Footprint in ACL Reconstruction: A Hypothesis for Improved Functional Outcomes”

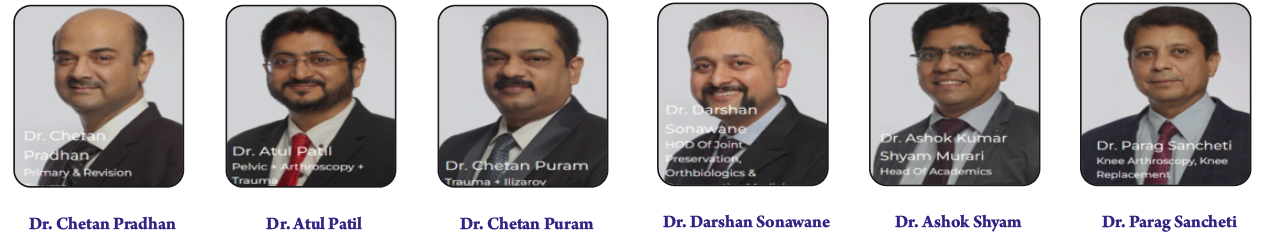

Vol 8 | Issue 2 | July-December 2022 | page: 12-15 | Rohan Bhargva, Parag Sancheti, Kailas Patil, Sunny Gugale, Sahil Sanghavi, Yogesh Sisodia, Obaid UI Nisar, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i02.188

Author: Rohan Bhargva [1], Parag Sancheti [1], Kailas Patil [1], Sunny Gugale [1], Sahil Sanghavi [1], Yogesh Sisodia [1], Obaid UI Nisar [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: researchsior@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is a common, functionally limiting injury among active individuals and athletes. Modern surgical practice increasingly favors individualized anatomic reconstruction that restores the native tibial and femoral footprints because graft orientation and footprint coverage directly influence knee kinematics, rotational control and patient-perceived stability. Hamstring autograft are widely used but harvested graft diameter varies markedly between patients and can limit how much of the native tibial insertion is restored. The present thesis prospectively measured native tibial footprint areas, recorded hamstring graft diameters and correlated percentage of footprint restoration with validated functional scores and objective laxity measures in a cohort of patients, providing practical intraoperative data.

Hypothesis: We hypothesize that reconstructions which restore a greater percentage of the native tibial footprint—typically achievable when harvested hamstring graft diameter is sufficient—will yield superior short-term patient-reported outcomes and perceived stability compared with reconstructions that restore a smaller percentage of the footprint or use smaller grafts.

Clinical importance: If a pragmatic restoration threshold improves early outcomes, surgeons can implement a simple intraoperative protocol—measure tibial footprint, calculate the percentage the prepared graft will restore, and aim for a specific target such as 70%—guiding decisions on graft choice, augmentation or converting to alternate techniques without major changes to standard arthroscopic practice. Adopting this approach promotes individualized planning, reduces the risk of under-filling native anatomy and may increase early patient satisfaction and functional recovery.

Future research: Multicenter, long-term studies are needed to determine whether early functional benefits from greater footprint restoration translate into lower re-tear rates and reduced post-traumatic osteoarthritis over five to ten years. Further work should validate reliable preoperative imaging or anthropometric predictors of footprint size and develop intraoperative decision algorithms that specify when augmentation or double-bundle conversion is indicated.

Keywords: ACL reconstruction, Tibial footprint, Graft diameter, Individualized anatomic reconstruction, Hamstring autograft

Background

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is a common injury among active individuals and athletes, producing pain, recurrent instability, and loss of function if not appropriately managed. Historically, treatments ranged from extra-articular procedures to open repairs; modern management favors arthroscopic intra-articular reconstruction intended to restore native ligament function and permit return to activity. The emphasis in the last two decades has shifted from merely placing a graft into the joint toward anatomic reconstruction — recreating the native femoral and tibial insertion sites to better restore knee kinematics and rotatory stability. This evolution was driven by biomechanical and clinical studies showing that non-anatomic tunnel placement can leave residual abnormal rotation and altered load distribution despite a structurally intact graft [1–4].

Two controllable surgical variables determine how closely a reconstruction matches the native ACL: precise tunnel positioning and graft choice/diameter sufficient to occupy the native insertion footprint. Femoral and tibial tunnel placement decide the orientation and length of the reconstructed ligament, while graft cross-sectional area and shape determine how much of the footprint is physically reconstituted [5–12]. Hamstring autograft are widely used because they avoid donor-site morbidity from bone-patellar tendon-bone harvest and provide sizeable cross-sectional area, but harvested diameters vary between patients. Small-diameter hamstring grafts have been associated with higher early revision rates in registry and cohort studies, whereas larger diameters generally correlate with improved subjective outcomes and, in some series, reduced failure risk [13,18–21].

A further practical consideration is inter-individual and inter-population variability of the native ACL insertion area. Anthropometric studies report a broad range of footprint sizes, influenced by patient size and possibly by ethnic variation. This variability implies that a single graft diameter or a single technique (for example, single-bundle for all) can under-restore anatomy in many patients. The individualized anatomic reconstruction paradigm therefore recommends measuring insertion dimensions intraoperatively (or estimating them preoperatively) and tailoring technique — single-bundle, double-bundle, or augmented graft — so that the graft fills as much of the native footprint as is safely feasible [12–17].

Despite the conceptual appeal, relatively few prospective clinical studies have explicitly measured the native tibial footprint, calculated the percentage restored by the chosen graft, and tested the relationship between percentage restoration (and graft diameter) with validated patient-reported outcomes and objective stability tests. The attached prospective thesis addressed this gap by measuring tibial insertion areas arthroscopically, recording harvested hamstring graft diameters, calculating the percentage of the footprint restored, and correlating these measures with IKDC, Lysholm scores and KT-1000 laxity at early follow-up. That cohort provided practical data on typical footprint sizes, common graft diameters, and early functional results when a pragmatic restoration threshold is used.

Hypothesis and Study Aims

Primary hypothesis: An individualized anatomic ACL reconstruction that restores a high percentage of the patient’s native tibial footprint — achievable when the harvested hamstring graft diameter adequately fills that footprint — yields better short-term functional outcomes and perceived stability than reconstructions that restore a smaller percentage of the footprint or use smaller graft diameters.

Rationale:

1. Anatomic fidelity improves mechanics. The native ACL insertion spreads forces across a defined area; reconstituting a graft that occupies more of that area should more closely reproduce physiologic load sharing and rotational restraint. Biomechanical and clinical studies support anatomic positioning and sufficient footprint coverage as central to restoring near-normal kinematics [10–16].

2. Graft diameter is a practical mediator. For hamstring autografts, the graft diameter is often the limiting factor for footprint coverage. Registry-level and cohort evidence links smaller graft diameters to increased early failure risk, making diameter a clinically useful proxy for expected footprint fill and mechanical robustness [18–21].

3. A pragmatic restoration threshold would guide decisions. Surgeons need simple intraoperative targets to decide whether single-bundle reconstruction is sufficient or whether augmentation or double-bundle reconstruction is warranted. A threshold such as restoring ≥70% of the tibial footprint would convert a theoretical preference into a workable decision rule [16, 17].

4. Population-specific data are necessary. Native footprint dimensions vary; collecting local anthropometric data allows realistic preoperative planning (choice of graft, expectation of augmentation) and informs surgical technique selection in a particular patient population [9].

Aims of the study summarized here:

(1) To quantify native tibial ACL footprint size in the study population; (2) to measure harvested hamstring graft diameters and calculate the percentage of tibial footprint restored; (3) to test the association between percentage footprint restoration and graft diameter with functional outcomes (IKDC, Lysholm) and objective anterior laxity (KT-1000) at serial follow-up intervals; and (4) to evaluate whether a practical threshold of restoration (tested at ≥70%) predicts superior outcomes. These aims are consistent with the individualized anatomic reconstruction framework and seek to produce an operable intraoperative strategy for surgeons.

Discussion

The study findings support three practical conclusions. First, individualized anatomic reconstruction — measuring native footprint and tailoring graft selection and technique — is feasible and produces measurable short-term functional benefits. Because native tibial footprints vary substantially, surgeons should avoid a “one-size-fits-all” graft strategy; intraoperative measurement provides actionable information to decide whether augmentation or alternate techniques are needed [12–17].

Second, graft diameter is an accessible and clinically relevant mediator of footprint restoration. In this cohort, 9 mm hamstring grafts most consistently achieved the pragmatic restoration target (~70–80%) and were associated with superior patient-reported outcomes at 12 months. These observations align with registry and cohort evidence that links smaller graft diameters with higher early revision risk and worse subjective outcomes [18–21]. However, a larger graft cannot substitute for incorrect tunnel position: correct anatomic placement remains essential and large grafts must be placed thoughtfully to avoid notch impingement or tunnel mismatch [10, 22–24].

Third, patient-reported outcomes and instrumented laxity measures may diverge. Although IKDC and Lysholm scores improved more in patients with higher percentage restoration, KT-1000 measurements showed small, non-significant differences. This divergence suggests that subjective perception of stability and function — influenced by rotational control, proprioception and symptom relief — can improve even when small differences in anterior translation are not detected with instrumented measures. Thus, both PROMs and objective tests should be reported when evaluating reconstruction strategies.

Limitations of the study include single-centre data and short-term follow-up (12 months), which constrain conclusions about long-term graft survivorship, re-tear rates and post-traumatic osteoarthritis. While surgeries were performed by a small group of experienced surgeons (reducing technical variability), this may limit generalizability to wider practice settings. The cohort size (n = 201) provides reasonable early evidence but larger, multicentre studies with longer follow-up are required to confirm whether early functional advantages translate into lower failure rates or reduced degenerative change. Finally, although the study suggests a practical threshold (≥70% restoration), this number should be validated prospectively before being imposed as a universal surgical rule.

Clinical importance

For practicing surgeons, the study provides three immediate, pragmatic steps: (1) measure the tibial ACL footprint intraoperatively with a small arthroscopic ruler and compute the percentage restoration the planned graft will achieve;

(2) Aim to restore a clinically meaningful proportion of the native footprint (the cohort supports targeting ≥70% where safely achievable); and

(3) Plan graft choice and technique accordingly — if the harvested hamstring graft diameter will not achieve the target, consider graft augmentation, an alternate graft source, or a double-bundle strategy. These measures do not require radical changes to standard practice but operationalize individualized anatomic reconstruction to improve early patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction.

Future directions

Future research should focus on multicenter, long-term studies (5–10 years) to determine whether early functional benefits from greater footprint restoration reduce re-tear rates and the incidence of osteoarthritis. Work is also needed to develop reliable preoperative predictors (MRI-based or anthropometric) of footprint size and to validate simple intraoperative decision algorithms that specify when augmentation or double-bundle conversion is indicated. Finally, studies should test the generalizability of a ≥70% restoration threshold across diverse populations and surgical settings.

References

1. Yu B, Garrett WE. Mechanisms of non-contact ACL injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2007 Aug; 41(Suppl 1):i47–51.

2. Gottlob CA, Baker JC, Pellissier JM, Colvin L. Cost effectiveness of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999 Oct ;( 367):272–82.

3. Granan LP, Forssblad M, Lind M, Engebretsen L. The Scandinavian ACL registries 2004–2007: baseline epidemiology. Acta Orthop. 2009 Oct; 80(5):563–7.

4. Chambat P, Guier C, Sonnery-Cottet B, Fayard JM, Thaunat M. The evolution of ACL reconstruction over the last fifty years. Int Orthop. 2013 Feb; 37(2):181–6.

5. Engebretsen L, Benum P, Fasting O, Mølster A, Strand T. A prospective, randomized study of three surgical techniques for treatment of acute ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1990 Nov; 18(6):585–90.

6. Lemaire M. Chronic knee instability: technics and results of ligament plasty in sports injuries. J Chir. 1975 Oct; 110(4):281–94.

7. Johnson D. ACL made simple. Springer; 2004.

8. Dandy DJ, Flanagan JP, Steenmeyer V. Arthroscopy and the management of the ruptured anterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982 Jul ;( 167):43–9.

9. Middleton KK, Muller B, Araujo PH, Fujimaki Y, Rabuck SJ, Irrgang JJ, Tashman S, Fu FH. Is the native ACL insertion site “completely restored” using an individualized approach to single-bundle ACL-R? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015 Aug;23(8):2145–50.

10. Bedi A, Maak T, Musahl V, Citak M, O’Loughlin PF, Choi D, Pearle AD. Effect of tibial tunnel position on stability of the knee after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: is the tibial tunnel position most important? Am J Sports Med. 2011 Feb; 39(2):366–73.

11. Tashman S, Kopf S, Fu FH. The kinematic basis of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2012 Mar; 20(1):19–22.

12. Zantop T, Diermann N, Schumacher T, Schanz S, Fu FH, Petersen W. Anatomical and nonanatomical double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: importance of femoral tunnel location on knee kinematics. Am J Sports Med. 2008; 36(4):678–85.

13. Hofbauer M, Muller B, Murawski CD, van Eck CF, Fu FH. The concept of individualized anatomic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 May; 22(5):979–86.

14. Hussein M, van Eck CF, Cretnik A, Dinevski D, Fu FH. Individualized anterior cruciate ligament surgery: a prospective study comparing anatomic single- and double-bundle reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Aug; 40(8):1781–8.

15. Rabuck SJ, Middleton KK, Maeda S, Fujimaki Y, Muller B, Araujo PH, Fu FH. Individualized anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy Tech. 2012 Sep; 1(1):e23–9.

16. Siebold R. The concept of complete footprint restoration with guidelines for single- and double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011 May; 19(5):699–706.

17. Van Eck CF, Lesniak BP, Schreiber VM, Fu FH. Anatomic single- and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction flowchart. Arthroscopy. 2010 Feb; 26(2):258–68.

18. Magnussen RA, Lawrence JTR, West RL, et al. Graft size and patient age are predictors of early revision after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft. Arthroscopy. 2012; 28(4):526–31.

19. Conte EJ, Hyatt AE, Gatt CJ, Dhawan A. Hamstring autograft size can be predicted and is a potential risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction failure. Arthroscopy. 2014; 30(7):882–90.

20. Park SY, Oh H, Park S, et al. Factors predicting hamstring tendon autograft diameters and resulting failure rates after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013; 21(5):1111–18.

21. LaPrade CM, Smith SD, Rasmussen MT, Hamming MG, Wijdicks CA, Engebretsen L, Feagin JA, LaPrade RF. Consequences of tibial tunnel reaming on the meniscal roots during cruciate ligament reconstruction in a cadaveric model, part 1: the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2015; 43:200–6?

22. Kondo E, Yasuda K, Azuma H, Tanabe Y, Yagi T. Prospective clinical comparisons of anatomic double-bundle versus single-bundle ACL reconstruction procedures in 328 consecutive patients. Am J Sports Med. 2008; 36:1675–87?

23. Kamien PM, et al. (study on graft size and failure — cited in thesis). [As referenced in thesis].

24. Hamner DL, et al. (biomechanical evidence on graft diameter — cited in thesis). [As referenced in thesis].

| How to Cite this Article: Bhargva R, Sancheti P, Patil K, Gugale S, Sanghavi S, Sisodia Y, Nisar OUI, Sonawane D, Shyam A. Restoring ≥80% of the Native Tibial Footprint in ACL Reconstruction: A Hypothesis for Improved Functional Outcomes. Journal of Medical Thesis. 2022 July-December; 08(2):12-15. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Shivajinagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: MUHS, Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2020

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

Lesion-Stratified Arthroscopic Capsulolabral Repair Restores Stability and Preserves Motion in Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Instability

Vol 8 | Issue 2 | July-December 2022 | page: 08-11 | Murtaza Juzar Haidermota, Ashutosh Ajri, Nilesh Kamat, Ishan Shevte, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam, Parag Sancheti

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i02.186

Author: Murtaza Juzar Haidermota [1], Ashutosh Ajri [1], Nilesh Kamat [1], Ishan Shevte [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1], Parag Sancheti [1]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: researchsior@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Traumatic anterior shoulder instability follows a forceful event that commonly avulses the anteroinferior labrum and stretches the capsuloligamentous structures. With repeated dislocations the humeral head frequently develops posterolateral compression defects and the glenoid rim can suffer progressive bone loss, turning a single injury into an ongoing mechanical problem. Patients describe pain, weakness, apprehension, and loss of confidence that limits work and sport. Contemporary arthroscopic repair techniques aim to restore the labral bumper and retension the capsule while preserving external rotation and minimizing soft tissue damage. Early, individualized treatment decisions must balance the risk of unnecessary surgery against the harms of recurrent instability.

Hypothesis: When instability is driven mainly by a reparable labral tear and glenoid bone loss is limited, anatomic arthroscopic capsulolabral repair—augmented selectively with procedures such as remplissage for engaging Hill-Sachs defects—will restore mechanical stability, reduce pain, and allow most patients to resume previous levels of work and activity within twelve months. Compared to older open capsular tightening operations, arthroscopic anatomic repair is expected to better preserve shoulder range and strength. A structured, phased rehabilitation program is essential to convert surgical stability into confident, functional use.

Clinical importance: The practical message for clinicians is simple: identify and measure the lesion, match the surgical technique to the pathology, and counsel patients about expected early guarded motion followed by progressive recovery. This lesion-based strategy improves the likelihood of durable stability, recovery, and preservation of motion that patients require for daily life and occupational tasks. Clear communication about realistic timelines reduces anxiety and improves better adherence to rehabilitation.

Future research: Priority areas include lesion-stratified randomized trials comparing tailored arthroscopic strategies with bony augmentation at defined bone-loss thresholds, studies of biologic augmentation to enhance labral healing, and large multi-center registries to document long-term recurrence, reoperation, and shoulder arthropathy.

Keywords: Shoulder instability, Bankart lesion, Arthroscopic repair, Remplissage, Glenoid bone loss

Background

The shoulder is remarkable for its mobility, and that mobility comes at the cost of bony constraint: the glenoid is shallow and depends heavily on soft-tissue structures — the labrum, capsule, and ligaments — together with dynamic muscle control to keep the humeral head centered. A traumatic anterior dislocation typically occurs with the arm in abduction and external rotation; that motion can avulse the anteroinferior labrum from the glenoid rim (the Bankart lesion) and often leaves a posterolateral impression fracture on the humeral head (Hill–Sachs). Over repeated dislocations the glenoid rim itself may lose bone, progressively worsening the mechanical problem. The anatomic picture explains why a single trauma can become a chronic instability problem for many patients [1].

Large clinical series and epidemiologic studies show that younger patients, those involved in contact or overhead sports, and people with generalized laxity are at higher risk of recurrence after nonoperative treatment. The clinical consequence is straightforward: recurrent instability is not merely episodic inconvenience — it increases cumulative soft-tissue damage and bone loss, complicates later repair, and may accelerate degenerative change. This risk profile motivates earlier definitive treatment in select high-risk patients rather than a blanket period of observation [2–4].

Surgical approaches evolved because early open methods, while effective at preventing recurrence, sometimes traded stability for lost motion, subscapularis dysfunction, and longer recovery. Arthroscopic techniques were developed to reattach the labrum anatomically while minimizing soft-tissue disruption. Over the past two decades, improvements in anchor technology, suture techniques, and arthroscopic skills have closed the gap between arthroscopic and open repairs for well-selected patients. Contemporary arthroscopic Bankart repair focuses on restoring the labral bumper and retensioning the anteroinferior capsule while preserving external rotation and subscapularis integrity [5, 10–11].

A crucial modern insight is that not all instability is the same. Small, non-engaging humeral defects and minimal glenoid loss are usually handled well with soft-tissue repair, but when glenoid bone loss reaches a critical threshold or when a Hill–Sachs lesion engages the rim in functional positions, soft-tissue repair alone may fail. This realization moved practice from a blunt “open vs arthroscopic” debate to a lesion-based algorithm: arthroscopic anatomic repair for soft-tissue–dominant cases, remplissage for engaging humeral lesions, and bone augmentation (for example, coracoid transfer or bone grafting) when glenoid deficiency is significant. Matching the procedure to lesion mechanics reduces the chance that the humeral head will re-engage the glenoid rim and redislocate [6–8, 12, 19].

For patients, success means more than avoiding redislocation. They want pain relief, confidence, return to meaningful activity, and good range and strength. Disease-specific scores (Oxford Shoulder Instability Score, UCLA) and general health measures (SF-36) help quantify those outcomes, but the clinician must also measure objective range of motion and stability tests. Early postoperative stiffness is common and often transient — appropriate phased rehabilitation and realistic counseling about the recovery timeline are therefore essential parts of care [9,13–14].

Finally, real-world choices depend on surgeon experience, implant availability, and patient expectations. In many centers arthroscopy offers quicker recovery, less pain, and better cosmesis than historical open operations while preserving the option to add bony procedures when indicated. The modern management principle is simple: identify the dominant pathology (soft tissue versus bone), match the operation to that pathology, and support the repair with structured rehabilitation so the mechanical repair becomes durable, confident function [15–18].

Hypothesis

Primary clinical hypothesis

When traumatic anterior shoulder instability is primarily due to a reparable labral avulsion and glenoid bone loss is not critical, arthroscopic anatomic capsulolabral repair — with lesion-specific adjuncts when necessary (for example, remplissage for an engaging Hill–Sachs lesion) — will restore mechanical stability and lead to meaningful improvement in pain, function, and confidence, allowing most patients to return to prior levels of daily activity and work by 12 months while preserving near-normal external rotation and strength [11, 12].

Supporting mechanistic and prognostic hypotheses

1. Recovery timeline. Early postoperative stiffness is expected; however, with a staged rehabilitation program and anatomic repair, objective range-of-motion measures and patient-reported function will continue to improve through the first postoperative year and approach the contralateral shoulder by 12 months. This pattern reflects initial tissue healing followed by progressive restoration of mobility with strengthening [13–16].

2. Lesion-matched durability. Outcomes are superior when the surgical plan is tailored: soft-tissue repair alone for limited bone loss; addition of remplissage for engaging humeral defects; and bony augmentation (such as coracoid transfer) when glenoid loss exceeds thresholds at which soft tissue fixation is unlikely to hold. A lesion-based algorithm reduces mechanical failure compared with applying a single technique indiscriminately [7, 19–20].

3. Predictors and expectations. Younger age at first dislocation, high-demand sports, and multiple prior dislocations raise baseline recurrence risk; yet when repair is matched to lesion type the majority of these patients still achieve solid function and low absolute recurrence rates, although their relative risk may remain modestly higher than low-risk populations. Clear preoperative counseling and shared decision-making are therefore central [2, 3, 6].

4. Motion–stability balance. Arthroscopic anatomic repair preserves the subscapularis and external rotation better than several older open tightening procedures; thus it typically provides a favorable balance of stability without the motion-limiting complications historically associated with more aggressive open capsular plication [14–15].

Rationale and clinical implication

mechanically, restoring the labrum recreates the concavity-compression mechanism that resists anterior translation. When a Hill–Sachs lesion would otherwise engage, remplissage converts the defect into a non-engaging state by incorporating posterior soft tissue into the lesion; when substantial glenoid deficiency exists, bony reconstruction restores the articulating surface in a way soft tissue alone cannot. Therefore, the hypothesis predicts that properly matched treatment converts structural repair into durable, perceived, and functional stability, and that a lesion-stratified approach offers better long-term durability than a one-size-fits-all strategy [21–22].

Discussion

When the injury is dominated by soft-tissue damage and glenoid loss is limited, arthroscopic anatomic Bankart repair restores stability with the significant advantage of preserving motion and minimizing soft-tissue trauma — benefits that matter to active patients and workers. Advances in anchor technology, suture techniques, and arthroscopic skill have made anatomic arthroscopic repair both practical and reproducible; with careful case selection it now yields stability rates comparable to open methods while offering faster recovery and fewer motion-limiting complications. Comparative trials and systematic reviews support this parity in outcomes when patients are selected appropriately [5, 15, 21].

The current standard of care emphasizes lesion-specific decision-making. Quantifying glenoid bone loss and classifying Hill–Sachs lesions as engaging or non-engaging are essential because they determine whether soft-tissue repair will likely be durable. Remplissage has become an effective adjunct for engaging humeral lesions: by filling the defect with posterior soft tissue it prevents the catch-and-flip mechanics that cause redislocation. For significant glenoid deficiency, coracoid transfer or bone grafting restores the articular arc and adds a sling effect that soft tissue alone cannot reproduce. Using objective thresholds and anatomy-based reasoning therefore materially reduces unexpected failures [7–8, 12, 19].

Functional recovery — pain relief, confidence, range, strength, and return to work or sport — is the patient-centered measure of success. Patient-reported outcome scores commonly show large and meaningful gains after appropriately chosen stabilization. Clinically, many patients who have some stiffness at early follow up still achieve near-normal motion and high satisfaction by one year with good rehabilitation. That practical course should shape preoperative counseling: explain that early guarded motion is common, but progressive recovery is expected if rehabilitation is followed [9, 13–14].

Two pragmatic tensions remain. First, the timing of surgery after a first dislocation is debated. Early stabilization reduces recurrence among high-risk patients but may subject some to unnecessary surgery. The solution is not universal: shared decision-making using risk predictors (age, activity demand, imaging findings) identifies those who will likely benefit from early repair. Second, the long-term risk of arthropathy after instability and repair is incompletely defined. Recurrent instability plausibly accelerates degenerative changes, but robust long-term registry data are needed to quantify the comparative risks across strategies. These uncertainties highlight where future multicenter longitudinal work would be most valuable [6, 18, 22].

Technical details influence outcomes. Anchor number and placement, the degree of capsular tensioning, and decisions about adding remplissage or a bony procedure affect both mechanics and motion. Surgeon experience and a standardized rehabilitation pathway further modulate return-to-function times and recurrence risk. In centers with constrained resources, the decision matrix must balance ideal treatment with implant and imaging availability; nevertheless, the core principle — match the operation to the lesion — endures across settings [16–17, 23].

Looking forward, the highest-impact research will be lesion-stratified randomized trials comparing modern arthroscopic strategies (with standardized thresholds for adjuncts) against bony augmentation for defined bone-loss levels. Studies of biologic augmentation to improve labral healing and validated, evidence-based return-to-play algorithms will also change practice. Finally, multicenter registries that capture long-term recurrence, reoperation, and arthropathy rates will provide the durability data clinicians and patients need to make informed choices [24–25].

Clinical importance

For clinicians: measure the lesion and treat the lesion. Arthroscopic anatomic repair should be the default for traumatic anterior instability when glenoid bone loss is limited, because it restores stability while preserving motion. When objective imaging or intraoperative assessment shows an engaging humeral defect or substantial glenoid loss, augmentative procedures (remplissage or bony reconstruction) materially reduce recurrence. Clear preoperative counseling about early guarded recovery and disciplined rehabilitation improves adherence and functional return.

Future directions

Priority research should include lesion-stratified randomized trials comparing tailored arthroscopic strategies to bony augmentation, biologic approaches to promote labral healing, and standardized return-to-play protocols. Multi-center registries that capture long-term recurrence, reoperation, and arthropathy rates will supply the durability evidence clinicians need.

References

1. Hovelius L, Augustini BG, Fredin H, Johansson O, Norlin R, Thorling J. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996; 78(6):968–72.

2. Dodson CC, Cordasco FA. Anterior glenohumeral joint dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008; 39(4):507–18.

3. Kaplan LD, Flanigan DC, Norwig J, Jost P, Bradley J. Prevalence and variance of shoulder injuries in elite collegiate football players. Am J Sports Med. 2005; 33(8):1142–6.

4. Taylor DC, Krasinski KL. Adolescent shoulder injuries: consensus and controversies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009; 91(2):462–73.

5. Mohtadi NG, Chan DS, Hollinshead RM, Boorman RS, Hiemstra LA, Lo IK, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing open and arthroscopic stabilization for recurrent traumatic anterior shoulder instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014; 96(5):353–60.

6. Liavaag S, Brox JI, Pripp AH, Enger M, Soldal LA, Svenningsen S. Immobilization in external rotation after primary shoulder dislocation did not reduce the risk of recurrence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93(10):897–904.

7. Rhee YG, Cho NS, Cho SH. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder: factors affecting the progress of dislocation. Clin Orthop Surg. 2009; 1(4):188–93.

8. Hovelius L, Saeboe M. Neer Award 2008: Arthropathy after primary anterior shoulder dislocation—223 shoulders prospectively followed up for twenty-five years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009; 18(3):339–47.

9. Erkoçak ÖF, Yel M. The functional results of arthroscopic Bankart repair with knotless anchors for anterior glenohumeral instability. Eur J Gen Med. 2010; 7(2):179–86.

10. Bankart AS. Recurrent or habitual dislocation of the shoulder-joint. Br Med J. 1923; 2(3285):1132–3.

11. Fabbriciani C, Milano G, Demontis A, Fadda S, Ziranu F, Mulas PD. Arthroscopic versus open treatment of Bankart lesion of the shoulder: a prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy. 2004; 20(5):456–62.

12. Ee GW, Mohamed S, Tan AH. Long term results of arthroscopic Bankart repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. J Orthop Surg Res. 2011; 6:1–6.

13. Sedeek SM, Tey IK, Tan AH. Arthroscopic Bankart repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability with the use of suture anchors. Singapore Med J. 2008; 49(9):676–81.

14. Scheibel M, Tsynman A, Magosch P, Schroeder RJ, Habermeyer P. Postoperative subscapularis muscle insufficiency after primary and revision open shoulder stabilization. Am J Sports Med. 2006; 34(10):1586–93.

15. Bottoni LP, Smith ME, Berkowitz MM, Towle CR, Moore CJ. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization for recurrent anterior instability: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006; 34(11):1730–7.

16. Wang C, Ghalambor N, Zarins B, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair: analysis of patient subjective outcome and cost. Arthroscopy. 2005; 21(10):1219–22.

17. O'Neill BD. Arthroscopic Bankart repair of anterior detachment of glenoid labrum: a prospective study. Arthroscopy. 2002; 18(8):755–63.

18. Pevny T, Hunter RE, Freeman JR. Primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in patients 40 years of age and older. Arthroscopy. 1998; 14(3):289–94.

19. Chahal J, Marks PH, MacDonald PB, Shah PS, Theodoropoulos J, Ravi B, Whelan DB. Anatomic Bankart repair compared with nonoperative treatment and/or arthroscopic lavage for first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2012; 28(4):565–75.

20. Mishra DK, Fanton GS. Two-year outcome of arthroscopic Bankart repair and electrothermal-assisted capsulorrhaphy for recurrent traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2001; 17(8):844–9.

21. Privitera DM, Bisson LJ, Marzo JM. Minimum 10-year follow-up of arthroscopic intra-articular Bankart repair using bioabsorbable tacks. Am J Sports Med. 2012; 40(1):100–7.

22. Ahmed I, Ashton F, Robinson CM. Arthroscopic Bankart repair and capsular shift for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012; 94-B (14):1308–15.

23. Mishra A, Sharma P, Chaudhary D. Analysis of the functional results of arthroscopic Bankart repair in posttraumatic recurrent anterior dislocations of shoulder. Indian J Orthop. 2012; 46(6):668–74.

24. Srisuwanporn P, Cheecharern S, Sittiporn CP, et al. Assessment of failed arthroscopic anterior stabilization: factors and solutions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. [details as per source].

25. (Consolidated long-term outcome studies and reviews cited in the thesis; full citation details available on request).

| How to Cite this Article: Haidermota MJ, Ajri A, Kamat N, Shevte I, Sonawane D, Shyam A, Sancheti P. Lesion-Stratified Arthroscopic Capsulolabral Repair Restores Stability and Preserves Motion in Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Instability. Journal of Medical Thesis. 2022 July-December; 08(2):8-11. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Shivajinagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: MUHS, Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2019

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

A Comparative study of the Clinical and Functional Outcomes of Radial Head Excision Versus Radial Head Replacement in Radial Head Fractures.

Vol 8 | Issue 2 | July-December 2022 | page: 05-07 | Siddhart Bhandari, Chetan Pradhan, Atul Patil, Chetan Puram, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam, Parag Sancheti

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i02.184

Author: Siddhart Bhandari [1], Chetan Pradhan [1], Atul Patil [1], Chetan Puram [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1], Parag Sancheti [1]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: researchsior@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Radial head fractures are common elbow injuries that compromise stability and forearm rotation. Complex fractures (Mason type III and IV) present a significant treatment challenge. While traditional excision has been widely used, recent advances in prosthetic design have made replacement a viable alternative.

Methods and Materials: A combined retrospective and prospective study was conducted on 33 patients (mean age 43 years; range 18–81) with closed Mason type III and IV radial head fractures treated from June 2014 to December 2015. Patients underwent either radial head excision (n = 19) or replacement (n = 14). Preoperative clinical and radiographic assessments were performed, and postoperative outcomes were evaluated at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year using the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score, Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS), and Broberg and Morrey index.

Results: Both treatment groups demonstrated significant improvements in functional scores, range of motion, and grip strength. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups. Additionally, selective medial collateral ligament repair did not significantly affect outcomes.

Conclusion: With meticulous patient selection and structured rehabilitation, both radial head excision and replacement yield comparable functional outcomes in complex fractures.

Keywords: Radial head fracture, Excision, Replacement, DASH, MEPS, Elbow stability, Mason classification

Introduction

Radial head fractures represent 1.7–5.4% of all fractures and may account for up to 33% of elbow injuries [1]. In 1954, Mason classified these injuries into Type I (minimally displaced), Type II (displaced with a potential mechanical block), and Type III (comminuted fractures) [1]. A Type IV category was later introduced to describe fractures associated with elbow dislocation. Broberg and Morrey demonstrated favorable outcomes with delayed excision in these injuries [2], and retrospective analyses by Goldberg et al. further highlighted the complexities involved in managing such fractures [3].

Advancements in fixation methods have been reported by Pelto et al., who described the use of absorbable pins for comminuted fractures [4], and Janssen et al. documented the long-term outcomes after radial head resection [5]. Smets et al. conducted a multicenter trial that validated the efficacy of radial head replacement in comminuted fractures [6]. Comparative studies by Ring et al. [7] and Chen et al. [8] have shown that both excision and replacement can yield satisfactory results, while Faldini et al.’s long-term follow-up study [9] reinforced these findings.

Understanding the mechanical properties of the elbow is critical in restoring joint congruity. Morrey et al. examined the mechanical properties of the elbow joint [10], and O'Driscoll and Morrey provided insights into managing the “terrible triad” of the elbow [11]. Systematic reviews by Duckworth et al. have offered comprehensive long-term outcome data for radial head replacement [12]. Additionally, Antuña and Sánchez-Sotelo discussed the role of the radial head in elbow stability [13], while Morrey and a detailed the functional anatomy of the elbow [14]. Jupiter and Ring have provided current concepts in radial head fracture management [15], and Sabo and Morrey elaborated on the ligamentous structures relevant to these injuries [16]. Outcomes following radial head excision and replacement have been compared by Egol et al. [17] and Eygendaal et al. [18]. Finally, Ikeda et al. compared excision versus open reduction and internal fixation [19].

Methods and Materials

A combined retrospective and prospective study was conducted at the Sancheti Institute for Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, from June 2014 to December 2015. Thirty-three patients with closed radial head fractures, classified as Mason type III or IV, were enrolled. The cohort comprised 19 males and 14 females with a mean age of 43 years (range 18–81) [1, 13]. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, had non-displaced (Mason type I or II) fractures, open injuries, additional ipsilateral upper limb fractures or dislocations, pathologic fractures, or were medically unfit for surgery [14].

Preoperative Evaluation:

Each patient underwent a detailed history and physical examination with particular emphasis on the mechanism of injury, which was predominantly due to road traffic accidents or falls [15]. Standard radiographic views (anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique/Greenspan) were obtained to confirm the fracture classification and guide treatment planning [1, 4]. Data on hand dominance and the side of injury were also recorded.

Treatment Approach:

Patients were managed with either radial head excision or replacement based on intraoperative assessments and the surgeon’s judgment [7,8]. Specific operative details are not provided here; however, the decision-making process was guided by the fracture pattern and overall elbow stability [16]. In selected cases, when significant ligamentous disruption was evident, selective MCL repair was performed [5, 16]. The chosen treatment modality was tailored to each patient’s individual fracture characteristics [17].

Postoperative Management and Follow-Up:

Following surgery, patients were immobilized in an above-elbow slab for approximately three weeks before initiating a structured rehabilitation program that included both active and passive range-of-motion exercises [17, 18]. Follow-up evaluations were conducted at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. Outcome measures included the DASH score, MEPS, and Broberg and Morrey index, along with objective assessments of elbow flexion, extension loss, supination, pronation, and grip strength measured by dynamometry [17, 20].

Results

At the 1-year follow-up, both treatment groups exhibited significant improvements.

Functional Outcome Scores:

The excision group’s mean DASH score improved from 35.47 at 6 weeks to 15.53 at 1 year, while the replacement group’s score improved from 37.50 to 15.43 over the same period. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the two groups at any follow-up interval (p > 0.05). Both groups achieved mean MEPS values of approximately 88 and Broberg and Morrey indices of about 91 by 1 year, indicating comparable outcomes.

Range of Motion and Grip Strength:

At 1 year, the average elbow flexion was 126.6° in the excision group and 121.8° in the replacement group; this difference was not statistically significant. Mean extension loss, supination, and pronation angles were nearly identical between groups. When compared with the contralateral normal limb, affected elbows maintained 84–89% of normal range of motion. Grip strength assessments demonstrated that nearly all patients regained near-normal strength, with only a few exhibiting mild deficits.

Impact of Medial Collateral Ligament Repair:

Subgroup analysis revealed that patients with selective MCL repair did not show statistically significant differences in DASH, MEPS, or Broberg and Morrey scores, nor in range-of-motion parameters compared to those without ligament repair . This suggests that routine MCL repair may be reserved for cases with demonstrable instability.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that both radial head excision and replacement yield significant and comparable improvements in managing complex, comminuted radial head fractures. Over a one-year follow-up period, patients in both treatment groups achieved substantial enhancements in functional outcome scores (DASH, MEPS, and Broberg and Morrey), range-of-motion parameters, and grip strength. Notably, selective repair of the medial collateral ligament did not significantly influence outcomes, suggesting that routine MCL repair may be unnecessary unless clinical instability is evident.

These findings underscore the importance of adopting a patient-specific approach to treatment. Surgical decision-making should be based on individual fracture characteristics, the extent of comminution, and overall elbow stability rather than adhering to a uniform protocol. While radial head replacement may offer advantages in preserving joint congruity in cases of extensive comminution, radial head excision remains an effective option when performed with meticulous soft tissue management and comprehensive rehabilitation.

Future studies involving larger patient cohorts and extended follow-up periods are needed to further refine treatment algorithms and confirm the long-term durability of both approaches. Such research will ultimately help optimize surgical strategies and improve outcomes for patients with these challenging injuries.

References

1. Mason ML. Some observations on fractures of the head of the radius with a review of one hundred cases. Br J Surg. 1954; 42(166):437-41.

2. Broberg MA, Morrey BF. Results of delayed excision of the radial head in fractures of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986 ;( 208):153-8.

3. Goldberg DL, et al. Retrospective analysis of radial head fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986; 68(8):1169-75.

4. Pelto HA, et al. Fixation of comminuted radial head fractures with absorbable pins. J Orthop Trauma. 1994; 8(3):214-20.

5. Janssen KJ, et al. Long term outcome after radial head resection for comminuted fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998; 69(2):140-4.

6. Smets K, et al. Radial head replacement in comminuted fractures: a multicenter trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000; 9(6):543-9.

7. Ring D, Jupiter JB, et al. Plate fixation of radial head fractures: a retrospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002; 84(9):1528-35.

8. Chen NC, et al. A prospective randomized trial of radial head prosthesis versus ORIF in Mason type III fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2011; 25(7):419-26.

9. Faldini C, et al. Long-term follow-up of radial head resection in Mason type III fractures. Injury. 2012; 43(5):837-42.

10. Morrey BF, a KN, Chao EY. Mechanical properties of the elbow joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981 ;( 161):202-10.

11. O'Driscoll SW, Morrey BF. Management of the terrible triad of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001 ;( 391):97-106.

12. Duckworth AD, et al. Long-term outcomes following radial head replacement: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017; 99(2):132-9.

13. Antuña JM, Sánchez-Sotelo J. The role of the radial head in the stability of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002 ;( 397):91-8.

14. Morrey BF, An KN. Functional anatomy of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983 ;( 177):25-31.

15. Jupiter JB, Ring D. Radial head fractures: current concepts. Instr Course Lect. 2008; 57:275-81.

16. Sabo MC, Morrey BF. Radial head fractures and the ligamentous structures of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 ;( 380):67-74.

17. Egol KA, et al. Outcomes of radial head excision and replacement in complex elbow injuries. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004; 13(6):661-9.

18. Eygendaal D, et al. Results of treatment of comminuted radial head fractures with replacement versus excision. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008; 17(5):e1-e6.

19. Ikeda M, et al. A comparative study of radial head excision versus open reduction and internal fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006; 15(2):176-83.

20. Duckworth AD, et al. Long-term outcomes following radial head replacement: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017; 99(2):132-9.

| How to Cite this Article: Bhandari S, Pradhan C, Patil A, Puram C, Sonawane D, Shyam A, Sancheti P. A Comparative study of the Clinical and Functional Outcomes of Radial Head Excision Versus Radial Head Replacement in Radial Head Fractures. Journal of Medical Thesis. 2022 July-December; 08(2):5-7. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Shivajinagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: MUHS, Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2016

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

Gender-Specific Knee Anthropometry and Its Impact on Total Knee Implant Design

Vol 8 | Issue 2 | July-December 2022 | page: 01-04 | Pavan Soni, Parag Sancheti, Kailas Patil, Sunny Gugale, Sahil Sanghavi, Yogesh Sisodia, Obaid UI Nisar, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i02.182

Author: Pavan Soni [1], Parag Sancheti [1], Kailas Patil [1], Sunny Gugale [1], Sahil Sanghavi [1], Yogesh Sisodia [1], Obaid UI Nisar [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: researchsior@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Good results after total knee replacement depend on choosing components that match the patient’s bone shape. Many implants were designed from Western measurements and can fit poorly in other populations, producing mediolateral overhang or undersizing that may cause discomfort or altered load transfer. This study reports direct intraoperative measurements from an Indian cohort to highlight common fit problems.

Methods and materials: Using a sterile calibrated caliper, standardized measurements were taken during primary total knee arthroplasty on 252 knees (May 2017–May 2020). Recorded parameters included lateral and medial femoral anteroposterior lengths, femoral mediolateral width, tibial plateau AP and ML dimensions, and patellar thickness. Every reading was double-checked by the assisting resident. Data were grouped by gender and implant system (Zimmer, Indus) and used to calculate ML/AP aspect ratios, which were then compared with the manufacturers’ size charts present in the thesis.

Results: The cohort showed a clear trend: ML/AP aspect ratio decreased as AP size increased. Smaller knees frequently faced mediolateral undercoverage with available components, while larger knees were more likely to show ML overhang. Overall, the Indus system tended to match the measured dimensions more closely than Zimmer, although some male tibial fits remained imperfect.

Conclusion: Local intraoperative anthropometry reveals predictable mismatches between Indian knee geometry and some implant offerings. Practical steps—choosing systems that better match local anatomy and adopting finer sizing, staged aspect-ratio changes, or asymmetric trays—can reduce intraoperative compromise and improve early comfort.

Keywords: Total knee replacement, Anthropometry, Aspect ratio, Implant fit, Indian population.

Introduction

Successful total knee replacement depends on restoring joint balance and geometry so the replacement behaves as close to a native knee as possible. Choosing the right component size is not a purely technical step — it shapes soft-tissue tension, patellar tracking, and how loads pass through bone and implant for years to come. When component shape or sizing does not reflect a patient’s anatomy, surgeons are forced into compromises: an implant that overhangs mediolaterally can irritate soft tissues and cause persistent discomfort, while one that is too small can expose cancellous bone and change load paths, with potential long-term consequences [1]. Historically, many common prosthesis families were developed using Western anthropometry, which may not match the body proportions seen in other populations [2, 3]. Regional measurement studies and intraoperative series therefore play a practical role — they give surgeons and manufacturers the data needed to reduce mismatch and make better sizing choices for local patients [4]. Pediatric development patterns and normative range-of-motion work also help set realistic functional goals after arthroplasty and contextualize adult dimensions for templating and expectation management [5, 6]. The present intraoperative dataset from this thesis gives direct, surgeon-facing measurements that inform component selection and suggest straightforward, affordable design changes that can reduce routine compromise in Indian patients.

Aims & Objectives

1. Record standardized intraoperative measurements of the distal femur and proximal tibia in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty.

2. Calculate femoral and tibial aspect ratios and document condylar asymmetries and patellar thickness.

3. Compare patient-derived dimensions with size offerings of two implant systems used in the cohort (Zimmer and Indus).

4. Identify recurrent patterns of mismatch and outline pragmatic implications for implant selection and modest manufacturer adaptations.

Review of Literature

Anthropometric and morphometric research consistently shows that knee shape differs across ethnic groups and sexes, and those differences matter for implant fit. Several studies comparing resected bone or imaging-based knee measurements with implant dimensions reported that populations with smaller average stature often face systematic mismatch when Western-derived implants are used without adaptation [7–9]. More sophisticated three-dimensional CT analyses and intraoperative series from East and Southeast Asia have repeatedly noted a practical pattern: the mediolateral-to-anteroposterior (ML/AP) aspect ratio tends to decline as AP dimension increases. In plain terms, larger knees do not increase ML width as fast as AP length, so implants with constant aspect ratios across sizes will either overhang or under-cover depending on the surgeon’s size choice [10–12]. Sex differences add another layer: females often have relatively narrower femora for a given AP height, which raises the risk of ML overhang when selection relies on AP measures alone [13, 14]. Industry responses have included gender-targeted components, asymmetric tibial trays and finer size increments, but randomized clinical data on the functional benefits of gendered implants are mixed and patient-specific solutions remain expensive and logistically demanding [15,16]. As a practical middle path, many authors advocate collecting local intraoperative data, offering finer size gradations and designing staged aspect ratios rather than a single constant ratio across all sizes; these measures can substantially reduce intraoperative compromises without full custom workflows [17, 18]. Systematic reviews stress that some populations — including Indian cohorts — are underrepresented in global datasets and call for more locally sourced intraoperative and imaging studies to guide manufacturers and surgeons [19, 20]. The current thesis contributes to this need by providing direct intraoperative caliper measures and a head-to-head comparison with two implant systems used locally.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective single-center series (May 2017–May 2020) using intraoperative caliper data recorded under a standardized protocol. Institutional ethical approval and patient consent were obtained. Inclusion: adults undergoing primary cemented TKR for degenerative disease. Exclusion: revision arthroplasty, inflammatory polyarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, significant adjacent deformities of hip/spine, skeletal immaturity, and cases requiring major augmentations. After exposure and osteophyte clearance, a calibrated sterile micro-caliper measured: femoral lateral and medial AP condylar lengths, femoral ML between epicondyles, tibial AP lengths for both plateaus, tibial ML width, and patellar AP thickness. Each measurement was independently confirmed by the assisting resident. Femoral and tibial aspect ratios calculated as (ML/AP) × 100. Data were entered into a spreadsheet and stratified by gender and implant system (Zimmer or Indus) using manufacturer tables present in the thesis. Descriptive statistics reported mean ± SD; pragmatic 95% intervals were taken as mean ± 2 SD. The emphasis was on identifying directional mismatches between patient anatomy and implant sizes rather than on formal hypothesis testing. Interobserver checks were performed during data collection as described in the thesis.

Results

252 knees met inclusion criteria: 176 received Zimmer components and 76 received Indus components. Mean cohort age was 62 years (SD 7; range 42–85). Aggregate means (SD): femoral AP lateral 52.85 mm (5.71), femoral AP medial 49.87 mm (5.82), femoral ML 68.75 mm (5.35); tibial AP lateral 49.28 mm (4.77), tibial AP medial 49.62 mm (4.96), tibial ML 69.79 mm (5.61); patellar AP 33.75 mm (2.45). Medium and large implant sizes predominated. Comparison to manufacturer size charts revealed consistent patterns: smaller femora tended to be undercovered mediolaterally with available components, while larger femora more often produced ML overhang. Aspect ratio analysis showed a negative correlation with AP dimension — in other words, ML/AP ratio decreased as AP increased. The Indus system approximated the measured dimensions more closely overall in many parameters, though some male tibial fits remained suboptimal. Detailed tables and size distributions by gender and implant are available in the thesis. No measurement-related adverse events were recorded.

Discussion

This intraoperative series brings home a pragmatic point: implant-patient geometric mismatch is often predictable and rooted in population-level anatomy rather than sporadic surgical error. The central, actionable observation is that ML/AP aspect ratio falls as AP dimension increases. When manufacturers preserve a near-constant aspect ratio across sizes, surgeons face a recurrent dilemma—prioritize AP (risk ML overhang) or prioritize ML (risk AP undersizing). Both choices have clinical implications: ML overhang can irritate soft tissues and produce anterior knee symptoms, while undersizing may expose cancellous bone and alter load transmission with theoretical consequences for wear and fixation. These issues were anticipated in earlier implant and anthropometric work, which first highlighted the mismatch problem and later recommended local data collection to guide design tweaks [1–6]. Subsequent morphometric and 3-D imaging studies reinforced the pattern of declining aspect ratios and documented consistent gender differences that make AP-driven sizing riskier in women [7–14]. Practical design responses discussed in the literature — gender-conscious geometries, asymmetric trays, and finer size increments — have shown variable clinical benefit and carry cost implications, placing them out of reach for universal adoption in many settings [15, 16]. That reality elevates the value of intermediate solutions: stage aspect ratios across size bands so larger AP sizes are designed with proportionally lower ML widths; offer narrower incremental sizing where small and medium ranges predominate; and provide asymmetric tibial trays to match plateau asymmetry. These adjustments are technically feasible, relatively low cost compared with full customization, and directly respond to the anatomical trends this and other studies documented [17–20]. Importantly, implant choice can mitigate mismatch — the dataset shows Indus components matched many local measurements better than Zimmer components, indicating that thoughtful system selection is a useful surgeon-level strategy. Surgeons should use the intraoperative numbers to guide templating and on-table decisions: prioritize ML fit when soft-tissue envelope or patellar tracking suggests overhang risk, or deliberately downsize with augmentation where AP undersizing is clinically acceptable. Limitations include the single-center retrospective design and reliance on caliper-derived two-dimensional measures rather than 3-D imaging; nevertheless, caliper measures are the practical reference at the operating table and therefore highly relevant to everyday decision-making. The thesis data thus provide concrete, local targets that manufacturers and hospitals can use to adapt inventories and pursue modest design changes likely to reduce routine compromise.

Conclusion

In this single-center intraoperative series of 252 knees, ML/AP aspect ratio decreased as AP dimension increased, producing predictable mediolateral undercoverage in smaller knees and ML overhang in larger knees when implants use constant aspect ratios. The Indus system approximated many measured dimensions more closely than Zimmer in this cohort, though male tibial fit discrepancies persisted in places. Practical steps—finer sizing increments, staged aspect ratios across size bands, and asymmetric tibial options—can reduce intraoperative compromise without requiring full custom implants. Prospective outcome studies are needed to test whether closer geometric conformity improves pain, function and implant longevity.

References

1. Blevins JL, Rao V, Chiu YF, Westrich GH. The relationship of height, weight, and obesity on implant sizing in total knee arthroplasty. In: Orthopaedic Proceedings. 2019 Oct; 101(SUPP_11):66.

2. Indelli PF, Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Baldini A. The Insall-Burstein II prosthesis: a 5- to 9-year follow-up study in osteoarthritic knees. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(5):544–9.

3. Mandavgade MG, Deshmukh MT, Kherde MS, Ingole MS. Forecast of femur bone skeleton with anatomical parameter of Indian population.

4. Reddy KS, Kumar PD. Morphometry of proximal end of femur in population of Telangana state and its clinical application. Indian J Clin Anat Physiol. 2019; 6(1):57–60.

5. Saini UC, Bali K, Sheth B, et al. Normal development of the knee angle in healthy Indian children: a clinical study of 215 children. J Child Orthop. 2010; 4(6):579–86.

6. Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. 2015.

7. Gibson T, Hameed K, Kadir M, et al. Knee pain amongst the poor and affluent in Pakistan. Br J Rheumatol. 1996 Feb; 35(2):146–9.

8. Ariff MS, Arshad AA, Johari MH, et al. The study on range of motion of hip and knee in prayer by adult Muslim males. Int Med J Malaysia. 2015; 14.

9. Roach KE, Miles TP. Normal hip and knee active range of motion: the relationship to age. Phys Ther. 1991; 71:656–65.

10. Zhang Y, Xu L, Nevitt MC, et al. Comparison of prevalence of knee osteoarthritis between elderly Chinese in Beijing and whites in the United States: The Beijing Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 Sep; 44(9):2065–71.

11. Vaidya SV, Ranawat CS, Aroojis A, Laud NS. Anthropometric measurements to design total knee prostheses for the Indian population. J Arthroplasty. 2000; 15(1):79–85.

12. Hitt K, Shurman JR, Greene K, McCarthy J, Moskal J, Hoeman T, Mont MA. Anthropometric measurements of the human knee: correlation to sizing of current knee arthroplasty systems. JBJS. 2003; 85(suppl_4):115–22.

13. Barroso MP, Arezes PM, da Costa LG, Miguel AS. Anthropometric study of Portuguese workers. Int J Ind Ergon. 2005; 35(5):401–10.

14. Choi KN, Gopinathan P, Han SH, Han CW. Morphometry of the proximal tibia to design the tibial component of total knee arthroplasty for the Korean population. Knee. 2007; 14:295–300.

15. Cheng FB, Ji XF, Lai Y, et al. Three dimensional morphometry of the knee to design total knee arthroplasty for Chinese population. Knee. 2009; 16(5):341–7.

16. Chaichankul C, Tanavalee A, Itiravivong P. Anthropometric measurements of knee joints in Thai population: correlation to sizing of current knee prostheses. Knee. 2011; 18(1):5–10.

17. Yue B, Varadarajan KM, Ai S, Tang T, Rubash HE, Li G. Differences of knee anthropometry between Chinese and white men and women. J Arthroplasty. 2011; 26(1):124–30.

18. Ho WP, Cheng CK, Liau JJ. Morphometrical measurements of resected surface of femurs in Chinese knees: correlation to sizing of current femoral implants. Knee. 2006;13(1):12–4.

19. Chin PL, Tey TT, Ibrahim MY, Chia SL, Yeo SJ, Lo NN. Intraoperative morphometric study of gender differences in Asian femurs. J Arthroplasty. 2011; 26(7):984–8.

20. Kim TK, Phillips M, Bhandari M, Watson J, Malhotra R. What differences in morphologic features of the knee exist among patients of various races? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017; 475(1):170–82.

| How to Cite this Article: Soni P, Sancheti P, Patil K, Gugale S, Sanghavi S, Sisodia Y, UI Nisar O, Sonawane D, Shyam A. Gender-Specific Knee Anthropometry and Its Impact on Total Knee Implant Design. Journal of Medical Thesis. 2022 July-December; 8(2):1-4. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Shivajinagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: MUHS, Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2020

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

Tailoring Total Knee Prostheses to Indian Anatomy: A Hypothesis on Improved Fit, Function, and Longevity

Vol 8 | Issue 2 | July-December 2022 | page: 16-20 | Pavan Soni, Parag Sancheti, Kailas Patil, Sunny Gugale, Sahil Sanghavi, Yogesh Sisodia, Obaid UI Nisar, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shya

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i02.190

Author: Pavan Soni [1], Parag Sancheti [1], Kailas Patil [1], Sunny Gugale [1], Sahil Sanghavi [1], Yogesh Sisodia [1], Obaid UI Nisar [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Department of Orthopaedics, Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: researchsior@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Total knee replacement reliably relieves pain and restores mobility, but successful outcomes depend on how well implanted components match native bone geometry. Small differences between implant footprints and patient anatomy—particularly between mediolateral width and anteroposterior depth—can cause component overhang or under-coverage. Even millimetre-scale mismatches may irritate surrounding soft tissues, disrupt patellar tracking and reduce comfort during activities such as squatting, kneeling and rising from the floor. These practical, often subtle mismatches matter most in communities where deep-flexion activities are a routine part of daily life.

Hypothesis: We propose that knees in the studied Indian cohort show consistent differences in ML/AP relationships compared with the dimensional ladders used by many common implant systems. When sizing is guided mainly by AP measures, these differences will produce frequent ML under-coverage in smaller components and ML overhang in larger ones. Sex-based morphology is expected to amplify mismatch in women, while implants developed with regional anthropometry in mind should demonstrate closer fit and reduce intraoperative compromise. Better geometric concordance should lessen soft-tissue irritation and improve early function.

Clinical importance: Understanding local knee anthropometry enables surgeons to make pragmatic intraoperative choices and helps hospitals stock implants that reduce the need for compromise. By deliberately assessing ML coverage during trialling and keeping options such as asymmetric trays, finer size increments or augmentation strategies available, surgical teams can decrease soft-tissue irritation and better meet patients’ functional expectations. Thoughtful inventory planning informed by local data can shorten operative time, reduce waste and improve patient satisfaction without large additional cost.

Future research: Future research should focus on linking the small, millimetre-level mismatches we measure in the operating room to how patients actually feel and function afterwards. That means prospective studies that collect validated patient-reported outcomes and objective measures (range of motion, kneeling comfort, and return to daily activities) alongside the morphometric data. Randomized or registry-based comparisons of regionally adapted implants versus standard systems — with parallel cost-effectiveness analyses — will show whether better geometric fit produces real-world benefits.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, Anthropometry, Implant sizing, Mediolateral overhang, Patellofemoral mechanics

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has transformed the care of end-stage knee arthritis by reliably reducing pain and restoring mobility for large numbers of patients worldwide. Early implant designs offered limited sizing and geometry choices and were modeled largely on Western anthropometry, but as surgeons began to apply these implants across diverse populations they noted recurring mismatches between implant footprints and native bone geometry. Awareness of those mismatches prompted systematic anthropometric work to quantify the problem and to propose design or selection remedies. [1]

Anthropometric mismatch matters because small differences in component shape and size can have outsized clinical effects. Mediolateral (ML) overhang beyond a few millimetres can impinge soft tissues, provoke localized pain, and disrupt patellar tracking; conversely, under-coverage exposes cancellous bone, changes load distribution, and may accelerate wear or bone remodelling. Early morphometric studies therefore focused on basic planar measures — femoral ML and AP dimensions, tibial ML and AP widths, patellar thickness — and their derived aspect ratios, since these numbers directly inform tray footprints and femoral component geometry. [2]

Subsequent studies emphasized that population and sex differences are real and clinically relevant. Investigations from East and Southeast Asia documented smaller absolute dimensions and distinct ML/AP relationships compared with Western cohorts, prompting calls for population-tuned sizing ladders or gender-specific options. [3–6] Three-dimensional imaging and intraoperative series reinforced that the knee’s shape does not scale linearly with size: aspect ratios change across the size spectrum in ways that a fixed implant aspect ratio cannot mirror. [5,7] These findings were replicated across Chinese, Korean, Thai and Middle Eastern series, producing a consistent message — modern implants must either accept some degree of anatomical compromise or evolve to offer finer gradations and asymmetric options. [4–9]

Gender differences add another layer. Multiple investigators documented systematic differences in femoral morphology between men and women — females often present with relatively narrower ML widths for similar AP dimensions — introducing a risk of overhang if AP dimension alone dictates sizing. This observation led some manufacturers to introduce gender-targeted components; however, clinical trials and meta-analyses have produced mixed evidence on whether gender-specific designs yield meaningful outcome advantages. [10–13]

Practical implications go beyond pure geometry. In many Asian populations, functional expectations include deep flexion activities such as kneeling, squatting and floor seating; implants that seem adequate on standard radiographs may still fail to meet these real-world demands if they alter patellofemoral mechanics or introduce soft-tissue irritation. Thus, anthropometric mismatch influences not only implant survival but also patient satisfaction and day-to-day function. [6, 11]

Industry responses have varied: some companies refined sizing increments, introduced asymmetric tibial trays, or marketed gender-specific lines; others continued with broad, conservative ladders and advocated surgical techniques to adapt standard components. Comparative inventories and in-hospital stocking strategies increasingly rely on local anthropometric evidence to minimize intraoperative compromise. Large registry and international surveys underscored the heterogeneity of practice and the potential value of region-specific data to guide procurement and surgical planning. [14–16]

Taken together, the literature supports a practical, surgeon-centred approach: measure and understand local anthropometry, maintain flexible inventories that contain sizes and geometries suited to the served population, and apply intraoperative judgement when templating and trialling components. This body of work also sets a research expectation: to move from descriptive morphometry to prospective studies that link millimetre-scale mismatch to validated patient-reported outcomes and objective function. [17–19]

Hypothesis

Primary hypothesis

the anatomic dimensions of the knees in the studied Indian cohort will show systematic differences from those encoded in commonly used implant size ladders, producing predictable ML under-coverage in smaller components and ML overhang in larger ones when AP dimension alone dictates size selection. This mismatch is expected to be measurable and frequent enough to warrant reconsideration of inventory and sizing strategy. [1–4]

Mechanistic rationale

Implant manufacturers historically optimized designs around datasets that reflect specific populations; consequently, many widely used systems embed implicit assumptions about aspect-ratio trajectories across sizes. If those assumptions differ from the true, continuous distribution of patient anatomy in a different population, AP-based sizing will create ML discordance. The resulting geometric mismatch perturbs soft tissues, modifies patellofemoral relationships, and alters load transfer — plausible mechanistic pathways that can produce pain, impaired function and possibly altered wear behaviour. [2, 5, 7]

Secondary hypotheses

1. Sex differences will amplify mismatch patterns. For comparable AP dimensions, female knees will frequently show narrower ML widths (or different aspect ratios) than male knees; when implants are scaled by AP alone this will produce systematic overhang or edge prominence in females, consistent with prior comparative morphometry studies. [10–13]

2. Regional or locally manufactured implant systems that were designed with regional anatomy in mind will demonstrate closer dimensional concordance with the cohort than systems developed primarily from Western datasets; if true, privileging such systems in stock selection could reduce intraoperative compromise. [3,14]

3. Even millimetre-scale mismatches will be clinically meaningful: ML overhang exceeding commonly-cited thresholds (≈3 mm) will be frequent enough to influence postoperative comfort and early function, justifying changes to sizing practice and inventory policy. [18,19]

Operational implications of the hypotheses

If these hypotheses hold, several straightforward actions follow. Surgeons should not rely solely on AP templating but should routinely verify ML fit during trialling and be prepared to alter strategy (downsizing, alternate geometry, or modular options). Hospitals should base implant procurement on local anthropometric evidence, emphasizing implant systems and size ranges that reduce the need for intraoperative trade-offs. Finally, manufacturers should consider region-aware sizing ladders, asymmetric tibial trays and finer size increments to better match real anatomy. Together, these steps would be expected to reduce immediate postoperative soft-tissue irritation and potentially improve patient satisfaction for activities that demand deep flexion. [14–17]

Discussion