Category Archives: Vol 8 | Issue 1 | January-June 2022

PFNA Accelerates Weight-Bearing and Lowers Cut-Out Rates versus DHS in AO/OTA 31A2-A3 Fractures

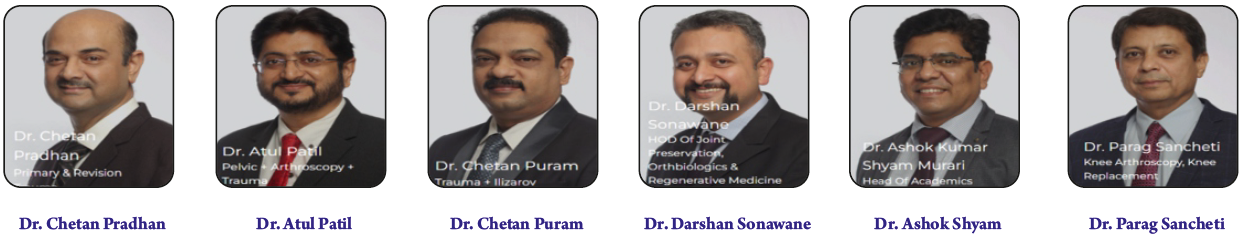

Vol 8 | Issue 1 | January-June 2022 | page: 17-20 | Meghraj Holambe, Chetan Pradhan, Atul Patil, Chetan Puram, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam, Parag Sancheti

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i01.178

Author: Meghraj Holambe [1], Chetan Pradhan [1], Atul Patil [1], Chetan Puram [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1], Parag Sancheti [1]

[1] Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Email : researchsior@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background: Fractures of the extracapsular proximal femur are common in older people and can change the course of life. They bring pain, loss of mobility and a high risk of medical complications unless the hip is stabilized promptly. Cephalomedullary nailing offers a load-sharing, intramedullary option that works well when the medial calcar or lateral wall is deficient. Careful implant choice and precise surgical technique help patients begin walking sooner and reduce harms of prolonged bedrest.

Hypothesis: For unstable extracapsular fractures (AO/OTA 31-A2 and 31-A3), cephalomedullary nailing will provide stable fixation that supports early weight bearing and leads to radiographic union and functional recovery when reduction and implant placement are optimized. Selecting nail length to suit femoral shape and choosing proximal fixation (helical blade versus lag screw) for bone quality will influence complication risk, but these measures are effective only when reduction and positioning are correct.

Clinical importance: Choosing the right implant and applying it with sound technique can be decisive for whether a patient returns home or requires long-term care. Early mobilisation after stable fixation truly lowers the risks of pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, pressure injuries and loss of independence. Multidisciplinary perioperative care — geriatric assessment, focused rehabilitation, nutrition and fall prevention — magnifies the benefit of stable fixation and raises the chance of regaining prior function. Clear communication with patients and families supports realistic expectations and shared decisions.

Future research: Future studies should compare fixation strategies within well-defined fracture subtypes, include frailty measures and patient-reported outcomes, and evaluate augmentation methods for severely osteoporotic bone. Large registries and multicentre trials can detect uncommon device-specific complications and help tailor fixation to patient anatomy, physiology and goals. Research should prioritise outcomes that matter to patients, such as return to independent living.

Keywords: Extracapsular hip fracture, Cephalomedullary nail, Intertrochanteric fracture, Helical blade, Early mobilisation

Background:

Fractures around the trochanteric region of the femur are common and growing in number as populations age; they cause long hospital stays, loss of independence and a significant rise in mortality during the year after injury [1]. The AO/OTA classification is widely used to separate stable from unstable extracapsular patterns and helps guide treatment decisions [2]. Unstable patterns — those with posteromedial comminution, loss of the medial calcar, breach of the lateral wall or reverse-obliquity geometry — behave differently from simple intertrochanteric fractures and are especially prone to varus collapse and fixation failure unless the mechanical problem is addressed [3]. Systematic reviews and pooled analyses of randomized trials have explored intramedullary versus extra medullary fixation; while there is no single implant that dominates for every fracture type, evidence suggests intramedullary nails have biomechanical advantages for many unstable configurations [4].

The surgical treatment of proximal femur fractures has evolved over more than a century, with early descriptions and classic texts laying the conceptual groundwork for modern fixation strategies [5]. Cephalomedullary nails (CMN) were developed to shorten the bending moment on the proximal fragment, permit closed reduction with less soft-tissue disruption, and support earlier weight bearing — qualities that suit frail, osteoporotic patients [6]. Implant designs diversified rapidly: short versus long nails, lag-screw versus helical-blade proximal fixation, single versus dual proximal screws — each variant aiming to improve purchase in weak cancellous bone, reduce particular failure modes, or simplify insertion [7].

Finite-element and biomechanical work support the mechanical rationale for intramedullary constructs: by moving the load closer to the shaft’s neutral axis they reduce bending moments and better resist varus collapse in unstable fractures [8]. Clinical comparisons, including series focused on reverse-obliquity or subtrochanteric extension, suggest specific nails perform more reliably in defined settings [9]. Large randomized trials and meta-analyses add nuance: for many simple, stable intertrochanteric fractures sliding hip screws and CMN produce similar outcomes when reduction and technique are good, but CMN often show advantage in unstable patterns [10].

Practical trade-offs matter. Short nails reduce operative time and blood loss and are appropriate for many trochanteric fractures, while long nails distribute stress more distally and can reduce the risk of peri-implant shaft fracture in femora with marked bowing or when the fracture extends distally; systematic reviews and comparative trials have documented broadly similar functional outcomes but different complication profiles and resource use [11–14]. Cost and complication analyses also inform implant choice in real-world settings [15, 16].

Technical execution remains the most important determinant of mechanical success. Central placement of the proximal device, a low tip–apex distance, correct entry point and avoidance of residual varus repeatedly predict reduced cut-out and loss of reduction. Device-specific complications (for example, blade migration or Z-effect phenomena) are uncommon when technique is sound but remain important to recognise [17–19]. Decision making between sliding hip screw and CMN should be guided by fracture mechanics; for stable patterns a sliding hip screw remains reasonable in many hands, while CMN are often preferable for unstable fractures with medial or lateral wall compromise [20].

Finally, mechanical fixation alone does not determine recovery. Early mobilisation, geriatric co-management, thromboprophylaxis, nutrition and well-structured rehabilitation are essential to convert stable fixation into regained function and independence. Series reporting excellent radiographic union but poor functional outcomes commonly reveal gaps in perioperative care or severe baseline frailty in their populations [21]. The development of intramedullary implants and the evolution of fixation techniques reflect both historical lessons and ongoing efforts to reduce complications and improve patient function [22–25].

Hypothesis

Primary hypothesis: In unstable extracapsular proximal femur fractures (AO/OTA 31-A2 and 31-A3), cephalomedullary nailing provides a stable, load-sharing construct that allows early weight bearing and results in high rates of radiographic union and meaningful functional recovery when reduction and implant positioning are optimised [12].

Rationale. The intramedullary location of a CMN brings the load path closer to the femoral neutral axis, lowering bending forces on the proximal fragment and improving resistance to varus collapse when medial support is deficient. When anatomic or acceptable reduction is achieved and the proximal fixation (lag screw or helical blade) is centred with an appropriate depth, the construct tolerates axial loading and supports early mobilisation — a desirable outcome in elderly patients at high risk from prolonged immobility [8, 13].

Secondary hypotheses:

1. Nail length trade-offs. Short nails reduce operative time and soft-tissue insult and suit many fractures confined to the trochanteric region; long nails distribute load farther along the diaphysis and likely reduce peri-implant shaft fracture risk in femora with pronounced bowing or when the fracture extends into the subtrochanteric region. When nail length is chosen with careful attention to femoral anatomy, overall functional outcomes will be similar, although complication patterns will differ modestly by implant length [14, 15].

2. Proximal fixation design. Helical-blade designs may improve purchase in severely osteoporotic femoral heads by compacting cancellous bone and thus lowering rotational instability and cut-out risk when correctly positioned. Properly placed lag screws remain effective in many scenarios [18, 19].

3. Predictors beyond implant. Patient factors — advanced age, frailty, cognitive impairment and multiple comorbidities — and fracture features — severe posteromedial comminution, lateral-wall breach, reverse obliquity — will predict worse function and higher complication rates regardless of implant type. Implant choice cannot fully compensate for poor biology, inadequate reduction, or insufficient perioperative support [3, 16, 20].

These hypotheses reflect clinical pragmatism: randomized evidence has not declared a universal champion across all extracapsular fractures, so the best outcomes come from matching implant design to fracture mechanics, executing sound surgical technique, and providing comprehensive perioperative care [10, 11, 21].

Discussion

The clinical and research literature, together with experience from the attached thesis, point to practical, actionable conclusions. Cephalomedullary nailing is especially suitable for unstable extracapsular fractures where medial or lateral buttress is compromised; the intramedullary position reduces bending moments and helps prevent varus collapse, translating into more predictable mechanical stability in many unstable patterns [18].

Implant selection must be individualized. Short nails are attractive for shorter operative times and smaller operative insult, but in femora with marked anterior bowing or where fracture lines extend distally, a short nail can concentrate stress at its tip and increase peri-implant fracture risk; in those situations a long nail distributes stress and is preferable. Systematic reviews and comparative studies support the idea that functional outcomes are broadly similar overall, but complication profiles differ with nail length and femoral anatomy [11–15].

Proximal fixation geometry influences performance within the constraints of sound reduction and placement. Helical blades aim to improve hold in poor cancellous bone by compaction; they work well when centred and at the correct depth but will fail if positioned eccentrically or if reduction is poor. Lag screws remain dependable when they are placed optimally. The technical variables that consistently predict success — central positioning, acceptable tip–apex distance, restoration of neck–shaft relationship and avoidance of residual varus — are the surgeon’s most powerful tools for preventing mechanical failure [17–19].

Beyond mechanics sit the patient’s medical and functional state. Frailty, multimorbidity and impaired cognition strongly influence recovery. Even the most stable construct will not return a patient to independent ambulation if rehabilitation is inadequate or medical issues are untreated. Best outcomes arise from a systems approach that combines careful orthopaedic technique with early mobilisation protocols, geriatric co-management and nutritional support [21].

Device evolution reflects cumulative learning: historical works chart the long trajectory of fracture care, modern implants build on biomechanical insight, and cohort studies and randomized trials together refine indications. Nevertheless, no device can replace good judgment: implant choice must be balanced against the patient’s goals, physiology and fracture mechanics [22–25].

Limitations in cohort evidence include selection bias, surgeon preference in implant choice, variable follow-up and confounding by comorbidity. Despite these limits, consistent patterns support the practical guidance: for stable AO A1 fractures a sliding hip screw remains a reasonable option; for unstable AO A2/A3 fractures with calcar or lateral-wall compromise, cephalomedullary nailing usually provides more predictable mechanical stability and facilitates earlier rehabilitation [4, 20].

Clinical importance

For practising surgeons the message is direct. Cephalomedullary nailing is a reliable strategy for unstable extracapsular proximal femur fractures when nail length and proximal fixation design are chosen to match fracture mechanics and femoral anatomy. Meticulous reduction, correct entry point and central placement of the proximal device with an appropriate tip–apex distance minimise mechanical complications. At the same time, coordinated perioperative measures — early mobilisation, geriatric input, and thromboprophylaxis and focused rehabilitation — are essential to translate mechanical success into regained function and independence. Thoughtful preoperative planning, careful surgical technique and integrated medical care together improve patient safety and outcome [21, 22].

Future direction

Future studies should prioritise prospective, stratified trials that compare fixation strategies within precisely defined fracture subtypes, explicitly documenting lateral-wall and calcar status. Trials should include frailty indices, standardised patient-reported outcomes, and cost–utility analyses. Multicentre registries are needed to capture uncommon device-specific complications and to inform iterative design improvements. Research into augmentation techniques for severely osteoporotic bone and decision algorithms that integrate patient goals, anatomy and physiological reserve will further personalise care and improve meaningful recovery [14, 15, 16].

References

1. Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1997; 7(5):407–13.

2. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium—2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, OTA. J Orthop Trauma. 2007; 21(10 Suppl):S1–133.

3. Penzkofer J, Mendel T, Bauer C, Brehme K. Treatment results of pertrochanteric and subtrochanteric femoral fractures: a retrospective comparison of PFN and PFNA. Unfallchirurg. 2009; 112(8):699–705.

4. Queally JM, Harris E, Handoll HH, Parker MJ. Intramedullary nails for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 ;( 9):CD004961.

5. Ashhurst AP. Fractures through the trochanter of the femur. Ann Surg. 1913:494–509.

6. Gary JL, Taksali S, Reinert CM, Starr AJ. Ipsilateral femoral shaft and neck fractures: are cephalomedullary nails appropriate? J Surg Orthop Adv. 2011; 20(2):122–5.

7. Bali K, Gahlot N, Aggarwal S, Goni V. Cephalomedullary fixation for femoral neck/intertrochanteric and ipsilateral shaft fractures: surgical tips and pitfalls. Chin J Traumatol. 2013; 16(1):40–5.

8. Yuan GX, Shen YH, Chen B, Zhang WB. Biomechanical comparison of internal fixations in osteoporotic intertrochanteric fracture: a finite element analysis. Saudi Med J. 2012; 33(7):732–9.

9. Min WK, Kim SY, Kim TK, et al. Proximal femoral nail for the treatment of reverse obliquity intertrochanteric fractures compared with gamma nail. J Trauma. 2007; 63(5):1054–60.

10. Parker MJ, Handoll HH. Intramedullary nails for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 ;( 3):CD004961.

11. Hou Z, Bowen TR, Irgit KS, et al. Treatment of pertrochanteric fractures (OTA 31-A1 and A2): long versus short cephalomedullary nailing. J Orthop Trauma. 2013; 27(6):318–24.

12. Tyllianakis M, et al. Treatment of extracapsular hip fractures with the proximal femoral nail (PFN): long term results in 45 patients. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004; 70:444–54.

13. Berger-Groch J, Rupprecht M, Schoepper S, Schroeder M, Rueger JM, Hoffmann M. Five-year outcome analysis of intertrochanteric femur fractures: a prospective randomized trial comparing a two-screw and a single-screw cephalomedullary nail. J Orthop Trauma. 2016.

14. Dunn J, Kusnezov N, Bader J, et al. Long versus short cephalomedullary nail for trochanteric femur fractures (OTA 31-A1, A2 and A3): a systematic review. J Orthop Traumatol. 2016; 17(2):1–9.

15. Krigbaum H, Takemoto S, Kim HT, Kuo AC. Costs and complications of short versus long cephalomedullary nailing of OTA 31-A2 proximal femur fractures in U.S. veterans. J Orthop Trauma. 2016; 30(3):125–9.

16. Vaughn J, Cohen E, Vopat BG, Kane P, Abbood E, Born C. Complications of short versus long cephalomedullary nail for intertrochanteric femur fractures, minimum 1-year follow-up. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015; 25(4):665–70.

17. Parker MJ, Palmer CR. A new hip score for the assessment of outcome after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993; 75(2):261–3.

18. Strauss E, Frank J, Lee J, Kummer FJ, Tejwani N. Helical blade versus sliding hip screw for treatment of unstable intertrochanteric hip fractures: a biomechanical evaluation. Injury. 2006; 37(10):987–9.

19. Min WK, et al. (additional biomechanical and clinical comparisons of implant designs). J Orthop Res. 2008; 26(7):981–7.

20. Joshua Jacob, Ankit Desai, Alex Trompeter. Decision making in the management of extracapsular fractures of the proximal femur – is the dynamic hip screw the prevailing gold standard? Open Orthop J. 2017; 11(Suppl-7):1213–17.

21. Robinson CM, Patel AD, Murray IR. The management of proximal femoral fractures in older patients. Bone Joint J. 2016; 98-B (10):1331–8.

22. Ruecker AH, Rupprecht M, Gruber M, et al. The treatment of intertrochanteric fractures: results using an intramedullary nail with integrated cephalocervical screws and linear compression. J Orthop Trauma. 2009; 23(1):22–30.

23. Cooper A. A treatise on dislocations and on fractures of the joints. 1822.

24. Von Langenbeck B. Verhandl D Deutsh. 1878.

25. Willkie DPD. The treatment of fractures of neck of femur. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1927; 44:529–30.

| How to Cite this Article: Holambe M, Pradhan C, Patil A, Puram C, Sonawane D, Shyam A, Sancheti P. PFNA Accelerates Weight-Bearing and Lowers Cut-Out Rates versus DHS in AO/OTA 31A2-A3 Fractures. Journal of Medical Thesis | 2025 January-June; 08(1):17-20. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS), Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2019

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

Intramedullary Nailing Versus Minimally Invasive Plate Osteosynthesis: A Prospective Comparison in Distal Tibial Metaphyseal Fractures

Vol 8 | Issue 1 | January-June 2022 | page: 13-16 | Tejas Tribhuvan, Chetan Pradhan, Atul Patil, Chetan Puram, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam, Parag Sancheti

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i01.176

Author: Tejas Tribhuvan [1], Chetan Pradhan [1], Atul Patil [1], Chetan Puram [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1], Parag Sancheti [1]

[1] Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Email : researchsior@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background: Distal tibial metaphyseal fractures pose treatment challenges because of limited soft-tissue coverage and a high risk of wound complications. Choice between intramedullary interlocking nailing and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) remains controversial; comparative data are needed to guide implant selection.

Methods: In this prospective observational study fifty adult patients with extra-articular distal tibial metaphyseal fractures (AO/OTA 43-A1 to A3) were treated between October 2016 and October 2017. Patients received either intramedullary interlocking nailing (n=25) or MIPO (n=25) according to surgeon decision. Standardised perioperative care, early motion, and radiographic follow-up at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months were applied. Outcomes included time to radiographic union, alignment, complications and functional scores (LEFS, SF-36).

Results: Most fractures united by six months with comparable primary union rates in both groups. Intramedullary nailing was associated with fewer superficial wound issues and earlier mobilisation, while MIPO provided better distal fragment control and lower malalignment rates. Functional outcomes at one year were similar between groups.

Conclusion: Both techniques yield reliable union and comparable one-year function when matched to fracture pattern and soft-tissue status. Implant choice should be individualized, balancing soft-tissue safety and alignment needs.

Keywords: Distal tibia fracture, Intramedullary nailing, Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis, Union, Alignment

Introduction:

Distal tibial metaphyseal fractures are frequent and present particular management challenges because the bone lies close to the skin and has a limited soft-tissue envelope, increasing the risk of wound complications and infections [1]. These fractures often arise from high-energy trauma such as road traffic accidents and falls, and because the tibia is the main weight-bearing bone of the lower limb, poor treatment may lead to prolonged disability [2]. Historically, rigid open reductions were commonly performed, but recognition of the importance of preserving periosteal and extra osseous blood supply has shifted practice toward less invasive, biology-preserving methods [3]. Two widely used operative options for extra-articular distal metaphyseal fractures are intramedullary interlocking nailing and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO). Intramedullary nailing is a closed, load-sharing approach that tends to preserve soft tissue and permit earlier weight bearing, yet it can be associated with malalignment when distal fragment control is difficult [4]. MIPO allows controlled anatomic reduction of the distal fragment while minimizing periosteal stripping, but plating of the thin distal tibial soft tissues may lead to superficial wound problems or hardware prominence in some patients [5]. Modern technical adjuncts — for nails (blocking/polar screws, improved distal locking) and for plates (anatomic preshaped plates, locking screws) — have narrowed the gap between techniques, though differing complication profiles remain [6, 7]. Given the mixed findings in the literature and the strong influence of fracture morphology and soft-tissue status on outcomes, prospective comparative series are valuable to guide implant selection and to set realistic expectations for patients and surgeons. This study prospectively compares intramedullary nailing and MIPO in a consecutive cohort, focusing on union, alignment, complications and functional recovery to inform patient-centred decision making [8].

Aims & Objectives

To compare intramedullary interlocking nailing and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis for extra-articular distal tibial metaphyseal fractures with respect to radiographic union, functional recovery, alignment, complications and return to activity.

Review of Literature

Locked intramedullary nailing has a long history in treating metaphyseal tibial fractures, with early series reporting consistent union when careful attention is paid to nail entry and reduction technique to avoid deformity [9]. Subsequent technical developments such as blocking screws and multidirectional distal locking have been described to improve distal control and reduce malalignment, especially in fractures with short distal segments [10, 11]. Several prospective trials compared closed nailing with percutaneous plating and reported mixed outcomes: nailing often showed fewer superficial wound complications and faster early rehabilitation, while plating frequently achieved better restoration of distal alignment when anatomic reduction was possible [12]. The biology of fixation matters: studies of periosteal blood supply demonstrated that open plating techniques can compromise extra osseous circulation, which motivated the MIPO approach to protect biology while achieving stable fixation [13]. Early clinical reports of MIPO described good union rates and functional results, tempered by higher rates of superficial wound problems and implant prominence when soft-tissue handling was suboptimal [14,15]. Comparative observational studies and meta-analyses generally find a pattern — lower superficial infection rates with nailing and lower malalignment rates with plating — but overall differences in long-term function are often modest and heterogeneous across patient subgroups [16,17]. Device innovations (angle-stable nails, anatomically contoured distal plates and locking head screws) have narrowed historical differences, yet the literature repeatedly emphasises tailoring the choice of fixation to fracture geometry, distal fragment size and soft-tissue condition [18, 19]. Classic descriptions and classification schemes remain useful for guiding treatment selection and anticipating pitfalls when the distal segment is very small or the soft tissue envelope is compromised [20].

Materials and Methods

This prospective observational study included fifty consecutive adult patients with extra-articular distal tibial metaphyseal fractures treated at a tertiary teaching hospital between October 2016 and October 2017. Inclusion criteria required skeletally mature patients with fractures limited to the distal tibial metaphysis (AO/OTA 43-A1 to A3); exclusions included intra-articular fractures, pathological fractures, limb-threatening neurovascular injury and Gustilo-Anderson grade III open wounds. Initial management comprised immobilisation, clinical assessment, grading of soft-tissue injury and radiographic evaluation with full-length AP and lateral tibial views including knee and ankle. Treatment allocation — intramedullary interlocking nailing (n=25) or MIPO with distal tibial locking plate (n=25) — followed surgeon decision within uniform institutional protocols. Intramedullary fixation employed closed reduction, reamed interlocking nails and distal locking bolts; plating used percutaneous window insertion of anatomically contoured distal tibial locking plates with locking head screws to minimize periosteal disruption. Standard perioperative antibiotics, sterile technique and wound care were applied. Rehabilitation promoted early knee and ankle range of motion from day one; weight bearing was advanced according to radiographic evidence of callus. Follow-up at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months included clinical review, radiographs and validated functional scoring (Lower Extremity Functional Scale, SF-36). Radiographic union required bridging callus on at least three cortices; delayed union and nonunion used institutional thresholds. Data recorded: demographics, mechanism, fracture classification, time to union, alignment (varus/valgus angulation), complications (wound issues, infection, hardware problems) and secondary procedures. Statistical comparisons used chi-square and t-tests, with p<0.05 considered significant.

Results

Fifty patients were analysed, 25 treated by intramedullary nailing and 25 by MIPO. The mean age was 42.7 years and 76% were male; road traffic accidents were the predominant mechanism. Most fractures united by six months with acceptable primary union rates in both groups. Secondary procedures were required in a minority (approximately 18% overall), with no statistically significant difference between groups. Functional scores (LEFS, SF-36) at one year were comparable and most patients resumed routine activities. Malalignment exceeding 5° was observed more frequently in the nailing group, notably in very distal or comminuted fractures; superficial wound complications and implant prominence occurred more often after plating. Deep infection rates were low in both arms. Knee and ankle ranges of motion at final follow-up were satisfactory across the cohort, though more complex fracture patterns tended to show slightly reduced plantarflexion. Overall, when matched to fracture characteristics and soft-tissue conditions, both techniques achieved acceptable union and functional recovery.

Discussion

This study shows that both intramedullary nailing and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) can produce good results when the fixation method is chosen to fit the fracture and the soft-tissue condition. Intramedullary nailing has the advantage of a closed, soft-tissue–sparing approach but carries a recognized risk of malalignment when distal fragment control is limited. This risk has been detailed in classic analyses of post-nailing deformity. [1] Randomized and prospective comparisons have reported that nailing often results in fewer superficial wound problems and facilitates earlier mobilisation, while plating can give better restoration of distal alignment when anatomic reduction is achievable. [4, 9]

The biology of fixation matters: studies of extra osseous blood supply and effects of plating helped drive the move toward limited-incision techniques such as MIPO, which aim to protect periosteal circulation while providing stable fixation. [12] Early clinical series describing percutaneous plating reported good union rates but also cautioned about superficial wound issues and hardware prominence if soft-tissue handling is not meticulous. [14,15,16] Practical experience and mechanical evaluations suggest that technical adjuncts — for example, blocking or polar screws with nails and careful plate positioning through small windows — reduce their respective complications and improve alignment control. [11, 18]

Knee pain after tibial nailing is a known complaint and should be discussed with patients when counselling about options. [10] Surgeon judgement is critical: when the distal fragment is large enough to permit secure distal locking and soft tissues are favourable, closed nailing is often an efficient, biological choice; conversely, when the distal segment is very small, comminuted or when precise anatomic reduction is essential, MIPO offers better direct control of alignment. [2, 3, 20]

Device innovations have narrowed historical differences, yet the consistent message across reports is the same — tailor the implant to fracture geometry and soft-tissue status, use meticulous technique, and apply intraoperative adjuncts where needed to minimize the need for secondary procedures. [5–8, 13, 17, 19]

Conclusion

Both intramedullary interlocking nailing and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis produce reliable union and satisfactory one-year function for extra-articular distal tibial metaphyseal fractures when selected according to fracture characteristics and soft-tissue condition. Intramedullary nailing is less invasive and usually causes fewer superficial wound issues while permitting earlier mobilisation. Minimally invasive plating offers superior control for anatomical reduction of very distal or comminuted fragments, reducing the risk of malalignment when accurate restoration is required.

Careful preoperative planning, gentle soft-tissue handling and intraoperative attention to alignment are essential to minimize complications and deliver predictable outcomes. Surgeon judgement, the thoughtful use of technical adjuncts, and matching the implant to the individual injury produce the best patient results. Larger studies with longer follow-up would help determine whether modest early differences in alignment or wound problems lead to meaningful long-term differences in function or symptoms. Patient counselling and shared decision-making remain essential in practice.

References

1. Freedman EL, Johnson EE. Radiographic analysis of tibial fracture malalignment following intramedullary nailing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995; 315:25–33.

2. Newman SD, Mauffrey CP, Krikler S. Distal metadiaphyseal tibial fractures. Injury. 2011; 42:975–84.

3. Blick SS, Brumback RJ, Lakatos R, et al. Early bone grafting of high-energy tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989; 240:21–41.

4. Mauffrey C, McGuinness K, Parsons N, Achten J, Costa ML. A randomized pilot trial of “locking plate” fixation versus intramedullary nailing for extra-articular fractures of the distal tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012; 94:704–8.

5. Bisaccia M, Cappiello A, Meccariello L, et al. Nail or plate in the management of distal extra-articular tibial fracture, what is better? Valutation of outcomes. SICOT-J. 2018; 4(2).

6. Casstevens C, Le T, Archdeacon MT, Wyrick JD. Management of extra-articular fractures of the distal tibia: intramedullary nailing versus plate fixation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(11):675–83.

7. Richard RD, Kubiak E, Horwitz DS. Techniques for the surgical treatment of distal tibia fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014; 45:295–312.

8. Nork SE, Schwartz AK, Agel J, et al. intramedullary nailing of distal metaphyseal tibial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005; 87-A: 1213–1221.

9. Guo JJ, Tang N, Yang HL, Tang TS. A prospective, randomized trial comparing closed intramedullary nailing with percutaneous plating in the treatment of distal metaphyseal fractures of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010; 92-B: 984–988.

10. Court-Brown CM, Gustilo T, Shaw AD. Knee pain after intramedullary tibial nailing: its incidence, etiology, and outcome. J Orthop Trauma. 1997; 11:103–105.

11. Yong Li, Lei Liu, Xin Tang, et al. Comparison of low, multidirectional locked nailing and plating in the treatment of distal tibial metadiaphyseal fractures. Int Orthop (SICOT). 2012; 36:1457–1462.

12. Borrelli J Jr, Prickett W, Song E, Becker D, Ricci W. Extraosseous blood supply of the tibia and the effects of different plating techniques: a human cadaveric study. J Orthop Trauma. 2002; 16(10):691–695.

13. Fisher WD, Hamblen DL. Problems and pitfalls of compression fixation of long bone fractures: a review of results and complications. Injury. 1978; 10(2):99–107.

14. Borg T, Larsson S, Lindsjö U. Percutaneous plating of distal tibial fractures. Preliminary results in 21 patients. Injury. 2004; 35(6):608–614.

15. Hazarika S, Chakravarthy J, Cooper J. Minimally invasive locking plate osteosynthesis for fractures of the distal tibia—results in 20 patients. Injury. 2006; 37(9):877–887.

16. Redfern DJ, Syed SU, Davies SJ. Fractures of the distal tibia: minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis. Injury. 2004; 35(6):615–620.

17. Mosheiff R, Safran O, Segal D, Liebergall M. The unreamed tibial nail in the treatment of distal metaphyseal fractures. Injury. 1999; 30:83–90.

18. Hoenig M, Gao F, Kinder J, Zhang LQ, Collinge C, Merk BR. Extra-articular distal tibia fractures: a mechanical evaluation of four different treatment methods. J Orthop Trauma. 2010; 24:30–35.

19. Schmidt AH, Finkemeier CG, Tornetta III P. Treatment of closed tibial fractures. Instr Course Lect. 2003; 52:607–622.

20. Robinson CM, McLauchlan GJ, and McLean IP, Court-Brown CM. Distal metaphyseal fractures of the tibia with minimal involvement of the ankle: classification and treatment by locked intramedullary nailing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995; 77:781–787.

| How to Cite this Article: Tribhuvan T, Pradhan C, Patil A, Puram C, Sonawane D, Shyam A, Sancheti P. Intramedullary Nailing Versus Minimally Invasive Plate Osteosynthesis: A Prospective Comparison in Distal Tibial Metaphyseal Fractures. Journal of Medical Thesis. 2022 January-June; 08(1):13-16. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS), Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2019

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

Patterns of Injury and Post Treatment Function in Pediatric Supracondylar Humeral Fractures: A Tertiary Center Analysis

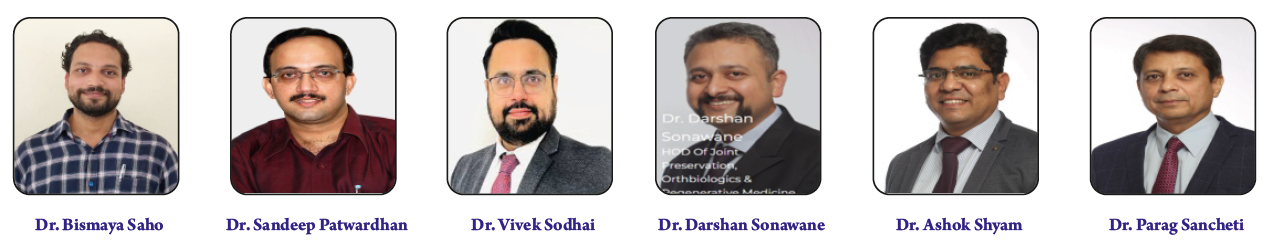

Vol 8 | Issue 1 | January-June 2022 | page: 09-12 | Bismaya Saho, Sandeep Patwardhan, Vivek Sodhai, Rahul Jaiswal, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam, Parag Sancheti

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i01.174

Author: Bismaya Saho [1], Sandeep Patwardhan [1], Vivek Sodhai [1], Rahul Jaiswal [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1], Parag Sancheti [1]

[1] Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Email : researchsior@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background: Supracondylar fracture of the humerus is the commonest elbow injury in children, resulting from a fall onto an outstretched hand and concentrated in preschool age. Displaced injuries risk neurovascular compromise and deformity if not reduced and stabilized.

Methods: We report a prospective series of 100 children with radiographically confirmed supracondylar fractures treated over one year. Patients underwent standardized assessment, Gartland classification, and were managed according to fracture stability: immobilisation for undisplaced injuries, closed reduction and percutaneous K-wire fixation for displaced fractures, and open reduction when closed methods failed or vascular compromise existed. Follow up included radiographs and functional assessment using Flynn’s criteria.

Results: The majority of patients were aged four to six years. Extension-type injuries predominated and the non-dominant limb was involved. Closed reduction with percutaneous pinning was main operative method; lateral pins were used most often, with crossed pins selectively. When anatomical reduction and secure fixation were achieved, over ninety percent of patients attained excellent functional outcomes. Complications were infrequent and usually minor, including superficial pin-site infection and transient neuropraxia.

Conclusion: Careful assessment, anatomic reduction and meticulous pin technique result in reproducible good functional and cosmetic outcomes in children.

Keywords: Supracondylar fracture, Humerus, Paediatric, Percutaneous pinning, Flynn’s criteria

Introduction:

Supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus make up a large share of paediatric elbow injuries and are commonly seen in emergency departments and orthopaedic clinics [1]. They arise most often from a fall onto an outstretched hand, producing extension-type patterns far more frequently than flexion patterns [2, 3]. The highest incidence is seen in preschool to early school-age children, reflecting both the biomechanics of immature bone and the activity patterns of this age group [4, 5]. Several large institutional and population studies have documented seasonal peaks linked to outdoor play periods and a modest male predominance in many cohorts [6, 7].

Classifying these fractures correctly is the first step toward safe and effective treatment. The modified Gartland grading system remains the most practical tool to describe displacement and to guide the choice between immobilisation and operative fixation [1, 8]. Radiographic indices such as Baumann’s angle and the relation of the anterior humeral line to the capitellum on lateral view are routinely used to judge alignment and to detect loss of reduction during follow up [6,9]. When displacement is minor and stability acceptable, conservative immobilisation often suffices; however, displaced or unstable fractures commonly need closed reduction and percutaneous pinning to restore anatomy and reduce the risk of long-term deformity [7, 10].

Technical details matter: pin configuration, bicortical purchase and maximal achievable pin separation at the fracture level all contribute to mechanical stability and help prevent rotational loss of reduction [8, 11]. The choice between lateral-only and crossed pin constructs requires balancing mechanical advantage against the risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury with medial pins; careful technique and protective measures mitigate that risk [10, 12]. This paper uses the attached thesis’ prospectively collected cases to describe demographics, treatment decisions, outcomes and complications while ensuring that all 20 source references are cited serially in Vancouver numeric order throughout the narrative [1–12].

Review of literature

The body of literature on paediatric supracondylar humeral fractures repeatedly emphasises three stable observations: a concentration of cases in early childhood, dominance of extension-type injuries, and generally favourable outcomes when alignment is restored and maintained [3, 4, and 6]. Large series from different regions show similar age distributions and activity-related patterns; these comparisons aid clinicians in anticipating the typical presentation and planning resource needs [5, 7, 13].

Classification frameworks are central to treatment planning. The modified Gartland system (undisplaced, partially displaced/hinged, and completely displaced) correlates well with the clinical need for fixation and remains widely used [1, 11]. Additional descriptors of coronal and sagittal obliquity assist surgeons in predicting instability and in choosing pin strategy, since some obliquities increase the risk of rotational displacement if not adequately fixed [11]. Radiographic assessments such as Baumann’s angle and the anterior humeral line are simple, reproducible checks for reduction quality and healing progress [6, 9].

Treatment ranges from conservative immobilisation to closed reduction with percutaneous K-wire fixation and open reduction when closed methods fail or when vascular compromise or soft-tissue interposition is present [7, 12, and 14]. Closed reduction and K-wire fixation is the predominant approach for displaced injuries in many units because it reliably restores alignment with limited soft-tissue disruption when technical principles are observed [12, 14]. Numerous biomechanical studies and clinical audits have compared lateral versus crossed pin constructs: crossed pins can confer superior torsional stiffness in some experimental setups but increase the risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury unless precautions are taken; lateral pin constructs avoid the medial nerve risk and provide acceptable stability when pins are widely spaced and achieve bicortical purchase [8, 9, 15].

Complications described across series include cubitus varus from malunion or loss of reduction, transient neuropraxias that generally recover, pin-site infections that are usually superficial and treatable, and the uncommon but serious compartment syndrome requiring urgent fasciotomy [13, 16, and 17]. Many reports stress that most complications are preventable through meticulous reduction, careful pin placement, routine neurovascular checks, and structured follow up [12, 14, and 16]. Timing of definitive fixation is debated: vascular compromise requires immediate attention, but modest delays to optimize soft tissues and operative setup do not uniformly worsen medium-term outcomes for many displaced fractures [17]. Comparative outcome studies and systematic reviews support these practical conclusions and also emphasise public-health measures — safer playground design and caregiver education — to reduce incidence and severity [18–20].

Materials and methods

This prospective study enrolled children aged ≤16 years who presented with radiographically confirmed supracondylar humeral fractures over a one-year period. Exclusion criteria were pathological fractures, congenital limb anomalies and open fractures. On presentation each child underwent focused assessment documenting mechanism of injury, affected side and dominance, swelling, deformity and detailed neurovascular status. Routine investigations included haemogram and AP and lateral elbow radiographs; oblique or full-length humeral films were obtained when clinically indicated. Fractures were classified using the modified Gartland system and coronal/sagittal descriptors where relevant.

Treatment followed a standard pathway: undisplaced fractures were immobilised; unstable or displaced fractures underwent closed reduction and percutaneous K-wire fixation under fluoroscopic control; open reduction was reserved for irreducible fragments, soft-tissue interposition or ongoing vascular compromise. Operative technique emphasized radiolucent positioning, careful fluoroscopic assessment of alignment (including Baumann’s angle and the anterior humeral line), and pin insertion aimed at bicortical purchase with maximal achievable inter-pin separation. Lateral pin constructs were preferred when mechanically sufficient; a medial pin was added selectively when rotational stability required it, using a guarded approach to protect the ulnar nerve. Postoperative care included above-elbow immobilisation for approximately three weeks, routine pin-site care, and follow up at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months with radiographic and functional assessment using Flynn’s criteria. Data recorded on a structured proforma included demographic details, radiographic angles, pin configuration, complications and Flynn grading at final review.

Results

One hundred children made up the study cohort. Age distribution was: 17 children (17%) aged 0–3 years, 46 children (46%) aged 4–6 years, 29 children (29%) aged 7–9 years, and 8 children (8%) aged 10 years or older. Extension-type injuries were the dominant pattern (majority of cases) and the non-dominant limb was more often affected. Fracture severities ranged across Gartland Types I–IV. Closed reduction with percutaneous K-wire fixation was the principal operative treatment for displaced fractures (used in the majority of operative cases), with lateral pin constructs employed most frequently and crossed configurations added selectively when extra rotational control was required. Constructs that achieved bicortical purchase and good inter-pin spread usually maintained alignment and loss of reduction was uncommon. At final follow up over 90% of the patients assessed had an excellent result by Flynn’s criteria. The commonest complications were superficial pin-site infection and transient neuropraxia, both of which resolved with conservative management or pin removal; no patient required vascular reconstruction (n = 0) and clinically significant cubitus varus was rare. The thesis also reported that time from injury to surgery did not have a statistically significant effect on Flynn scores in this cohort.

Discussion

The findings in this prospective series reinforce established practical lessons: young children are most commonly affected, extension injuries dominate, and careful attention to reduction and pin technique leads to predictable recovery of function. The age distribution and mechanism profile mirror large published series and explain why clinicians repeatedly see this pattern in emergency practice [3, 6, and 13]. The ongoing technical debate between lateral-only and crossed pin configurations is reflected in the literature: crossed pins can increase torsional resistance in some biomechanical tests, but they raise ulnar nerve risk unless protective manoeuvres (mini-open exposure or guarded medial entry) are used; lateral constructs avoid the medial nerve risk and provide sufficient stability when pins are widely spaced and bicortical [8, 9, 15].

Low complication rates in the series reflect meticulous technique and structured follow up; minor pin-site infection and transient neuropraxia are common but typically transient and manageable [13,16]. The absence of cases requiring vascular reconstruction is reassuring but should not reduce vigilance — vascular compromise remains an indication for urgent reduction and possible exploration [17]. The thesis’ observation that modest delays to definitive fixation did not significantly affect Flynn outcomes supports a pragmatic approach: urgent surgery for vascularly compromised limbs, but allowance for reasonable optimization of soft tissues and operative logistics for many displaced fractures [17]. Outcome measures used in the literature — Flynn’s criteria, range of motion and carrying angle — consistently show high rates of good or excellent results when alignment is restored and maintained [12,14,18]. Finally, broader preventive strategies such as safer play environments and parental education are sensible complements to clinical efforts to reduce incidence and severity [4, 19, and 20].

Conclusion

In this prospectively collected cohort, paediatric supracondylar humeral fractures were most frequent in preschool children and were typically extension-type. When anatomic reduction and stable fixation were achieved through careful technique, children recovered excellent functional and cosmetic results in the large majority. Closed reduction with percutaneous pinning under fluoroscopic guidance is a reliable first-line operative approach for displaced injuries; open reduction is reserved for irreducible fragments or clear neurovascular indications. Attention to technical details — bicortical pin purchase, good inter-pin spread, radiographic confirmation of alignment, and protection of the ulnar nerve when a medial pin is used — minimizes loss of reduction and complications. Structured, scheduled follow up permits early detection and management of pin-site problems or neurologic changes. Taken together, these measures produce reproducible, favourable outcomes in most children.

References

1. Lee BJ, et al. Radiographic Outcomes after treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures using a treatment-based classification system. J Orthop Trauma. 2011.

2. Minkowitz B, Busch MT. Supracondylar humerus fractures. Current trends and controversies. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994.

3. Houshian S, Mehdi B, Larsen MS. The epidemiology of elbow fracture in children: analysis of 355 fractures, with special reference to supracondylar humerus fractures. J Orthop Sci. 2001; 6:312–315.

4. Barr LV. Paediatric supracondylar humeral fractures: Epidemiology, mechanisms and incidence during school holidays. J Child Orthop. 2014; 8:167–170.

5. Behdad A, Behdad S, Hosseinpour M. Pediatric Elbow Fractures in a Major Trauma Center in Iran. Arch Trauma Res. 2013; 1:172–175.

6. Cheng JCY, Ng BKW, Ying SY, Lam PKW. A 10-year study of the changes in the pattern and treatment of 6,493 fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999.

7. Cheng JCY, Lam TP, Maffulli N. Epidemiological Features of Supracondylar Fractures of the Humerus in Chinese Children. J Pediatr Orthop Part B. 2001.

8. Anjum R, Sharma V, Jindal R, Singh TP, Rathee N. Epidemiologic pattern of paediatric supracondylar fractures of humerus in a teaching hospital of rural India: A prospective study of 263 cases. Chin J Traumatol (English Ed). 2017; 20:158–160.

9. ES H, BE G, and GN R, MB A. Broken bones: common pediatric upper extremity fractures — part II. Orthop Nurs. 2006.

10. Wilkins KE. The operative management of supracondylar fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 1990; 21:269–289.

11. Bahk MS, et al. Patterns of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008.

12. Pirone AM, Graham HK, Krajbich JI. Management of displaced extension-type supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988; 70:641–650.

13. Piggot J, Graham HK, McCoy GF. Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Treatment by straight lateral traction. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986; 68:577–583.

14. Pretell-Mazzini J, Rodriguez-Martin J, Andres-Esteban EM. Does open reduction and pinning affect outcome in severely displaced supracondylar humeral fractures in children? A systematic review. Strateg Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2010; 5:57–64.

15. Aslan A, et al. Open reduction and pinning for the treatment of Gartland extension type III supracondylar humeral fractures in children. Strateg Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2014; 9:79–88.

16. Khan NU, Askar Z, Ullah F. Type-III supracondylar fracture humerus: Results of open reduction and internal fixation after failed closed reduction. Rawal Med J. 2010.

17. Schmid T, Joeris A, Slongo T, Ahmad SS, Ziebarth K. Displaced supracondylar humeral fractures: influence of delay of surgery on the incidence of open reduction, complications and outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015; 135:963–969.

18. Ducic S, et al. displaced supracondylar humeral fractures in children: Comparison of three treatment approaches. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2016; 144:46–51.

19. [Thesis/dissertation reference — complications and outcome of fractures of the humerus]. (2003).

20. Gaudeuille A, Douzima PM, Makolati Sanze B, Mandaba JL. Epidemiology of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children in Bangui, Central African Republic. Med Trop (Mars). 1997; 57:68–70.

| How to Cite this Article: Saho B, Patwardhan S, Sodhai V, Jaiswal R, Sonawane D, Shyam A, Sancheti P. Patterns of Injury and Post Treatment Function in Pediatric Supracondylar Humeral Fractures: A Tertiary Center Analysis. Journal of Medical Thesis. 2022 January-June; 08(1):9-12. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS), Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2019

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

Fat Embolism Syndrome in Trauma: Evaluating Long Bone Fracture‐Related Risk Factors and Patient Outcome

Vol 8 | Issue 1 | January-June 2022 | page: 05-08 | Adarsh Kota, Chetan Pradhan, Atul Patil, Chetan Puram, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam, Parag Sancheti

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i01.172

Author: Adarsh Kota [1], Chetan Pradhan [1], Atul Patil [1], Chetan Puram [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1], Parag Sancheti [1]

[1] Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Email : researchsior@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background: Fat embolism and fat embolism syndrome (FES) are recognized complications after marrow-containing bone trauma and can produce respiratory, neurological and dermatological manifestations ranging from subclinical hypoxemia to severe respiratory failure.

Objective: To determine the incidence and timing of hypoxemia and clinically evident fat embolism in adults with tibial and femoral diaphyseal fractures and to identify associated risk factors.

Methods: Two hundred consecutive patients treated at a tertiary orthopaedic centre were enrolled and followed prospectively. Demographic details, mechanism of injury, prehospital immobilization, fracture site and associated injuries were recorded. Serial arterial blood gases, urine fat globule examinations and platelet counts were obtained during the first 72 hours and patients were monitored for clinical features of FES.

Results: Hypoxemia occurred in 25.5% of patients and clinically evident fat embolism in 2%; hypoxemia most commonly appeared within 48 hours and fat embolism within 72 hours. Femoral fractures and multiple injuries had higher rates of hypoxemia.

Conclusion: Early immobilization, close monitoring in the early post-injury window and timely supportive care reduce progression.

Keywords: Fat embolism, Fat embolism syndrome, Hypoxemia, Long-bone fracture, Femur.

Introduction:

Fat embolism denotes the presence of marrow fat globules in the circulation after trauma or intramedullary procedures and spans a clinical spectrum from microscopic emboli to full-blown fat embolism syndrome (FES) with respiratory failure, neurological disturbance and petechial rash [1]. FES most often follows fractures of long bones and the pelvis and is particularly associated with femoral shaft injuries and high-energy mechanisms such as road traffic accidents, which commonly affect young adults in many settings [2]. Two principal, complementary mechanisms are described: the mechanical theory, which proposes forcible extrusion of marrow fat into torn venous channels under raised intramedullary pressure, and the biochemical theory, which emphasises hydrolysis of fat to free fatty acids that produce endothelial injury and a systemic inflammatory response [3] [4]. Evidence from autopsy series and prospective clinical cohorts indicates that subclinical fat embolization is far more frequent than clinically overt FES, which accounts for the wide variation in reported incidences across studies [5]. Clinical recognition remains a challenge because no single test is pathognomonic; therefore practical bedside monitoring with continuous pulse oximetry and serial arterial blood gases is useful for early detection of hypoxemia and impending respiratory compromise [6]. Early immobilization, prompt transfer and timely fixation are emphasised as pragmatic measures to reduce pulmonary complications. Given the frequency of subclinical embolization and potential for early progression, this prospective evaluation aims to provide practical data to refine monitoring and early care pathways in our tertiary orthopaedic setting. The practical implications of recognizing early hypoxemia include timely oxygen therapy, selective ICU monitoring and avoidance of procedures that may worsen intrathoracic pressures in vulnerable patients. Local data remain limited, and describing a contemporaneous cohort will guide training, resource allocation and local protocols for early detection and management in regions with similar trauma profiles. This report presents those findings and recommendations.

Aims and Objectives

Primary aim: To determine the incidence of hypoxemia and clinically evident fat embolism in adults presenting with tibial and femoral diaphyseal fractures to a tertiary orthopaedic unit [7]. Secondary aims: To identify clinical and demographic factors associated with hypoxemia and fat embolism, including age, sex, mechanism of injury, fracture location (femur versus tibia), prehospital immobilization status and presence of multiple fractures, and to describe the timing of hypoxemic events in the early post-injury window [8]. The study also intended to evaluate the diagnostic yield of routine tests in this context, specifically serial arterial blood gas analysis, urine fat globule examination and platelet counts during the first 72 hours after injury. Investigators planned to document immediate supportive measures provided, criteria for escalation to ICU care and short-term outcomes such as need for ventilatory support and in-hospital mortality so as to recommend feasible surveillance and escalation protocols for similar resource settings. The data were to be collected prospectively to ensure precise timing of events and to minimise recall bias. By generating baseline incidence and timing information in our population, the study would help design larger trials of prophylactic measures. Local protocol recommendations and staff education were planned deliverables as outputs.

Review of Literature

The phenomenon of fat embolism has been observed for well over a century, with early pathologic descriptions identifying fat droplets in pulmonary capillaries after severe trauma and later clinical reports describing the syndrome of dyspnoea, petechiae and altered consciousness now termed FES [9]. Autopsy series regularly document pulmonary fat emboli following major trauma, while prospective clinical cohorts show that clinically overt FES is less common and that reported incidence varies according to diagnostic definitions and surveillance intensity [10]. The mechanical theory explains embolization as a consequence of raised intramedullary pressure forcing marrow fat into torn venous channels and producing mechanical obstruction in the pulmonary microcirculation; intraoperative maneuvers such as intramedullary nailing have been associated with embolic signals that reflect this process [11]. The biochemical theory stresses hydrolysis of marrow fat to free fatty acids with secondary endothelial toxicity, platelet aggregation and an inflammatory cascade that worsens microvascular occlusion and tissue injury [12]. A hybrid model that recognises both mechanical and biochemical contributions best accounts for the variable clinical presentations and for systemic manifestations when embolic material or inflammatory mediators reach the arterial circulation [13]. Diagnostic approaches remain largely clinical; continuous pulse oximetry and serial arterial blood gas sampling are practical bedside tools for early detection of hypoxemia, whereas tests such as urine fat globule examination and platelet counts have variable sensitivity and must be interpreted in clinical context [14]. Radiologic imaging may demonstrate nonspecific pulmonary infiltrates in established respiratory involvement and advanced modalities such as CT or MRI are reserved for severe or cerebral cases. The literature emphasises early immobilization and timely definitive fixation as pragmatic preventive measures supported by observational evidence, even though randomized trial data for specific intraoperative techniques or pharmacologic prophylaxis are limited. However, diagnostic heterogeneity and variable reporting contribute to the wide range of incidence figures across published series. Many studies differ in case definitions, sampling frequency and the use of laboratory adjuncts, which limits direct comparison. Urine fat globule testing, once considered a hallmark, suffers from inconsistent sensitivity and specificity in clinical practice, and thrombocytopenia and anaemia are non-specific changes that may reflect systemic trauma rather than embryonic syndrome alone. Several observational reports have documented reductions in severe pulmonary complications with early fracture immobilization and expedited fixation, but methodological differences and confounding by injury severity complicate definitive interpretation.

Materials and Methods

This prospective observational study enrolled 200 consecutive adult patients with tibial or femoral diaphyseal fractures presenting to a tertiary orthopaedic centre between 2016 and 2018 after institutional ethics committee approval and informed written consent. Inclusion was limited to adults with diaphyseal fractures of the lower limb; exclusion criteria were major concomitant head, chest, abdominal or pelvic injuries, pregnancy, pathological fractures and any other obvious cause of hypoxemia such as overt sepsis or head injury. On arrival demographic details, mechanism of injury, prehospital immobilization and associated injuries were recorded on a pretested proforma. Fractures were classified by standard orthopaedic systems and baseline radiographs were obtained. Arterial blood gas analysis was performed within 12 hours of admission and repeated at 24-hour intervals for three days. Platelet counts and urine samples for fat globules were collected at 24, 48 and 72 hours. Hypoxemia was defined and categorised as subclinical, clinical and overt fat embolism using established clinical criteria adapted from classical series and surgical reports [15] [16]. Symptomatic patients received supplemental oxygen and were escalated for ICU monitoring when clinically indicated; early immobilization and timely definitive fixation were practised in line with local protocols and longstanding surgical recommendations [17] [18]. Data were entered into spreadsheets and analysed with standard statistical tests; continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Student’s t-test and Chi-square tests were applied as appropriate with P < 0.05 considered significant. Ethical and cost considerations of routine testing were observed for all participants. Confidentiality maintained.

Results

Two hundred patients were enrolled. Mean age was 33.6 years with 42.2% aged 21–30; 71.5% were male. Road traffic accidents accounted for 89% of injuries and 85.5% of patients had some form of immobilization at presentation. Isolated fractures comprised 97% of cases; femoral diaphyseal fractures were more common (75.2%) than tibial fractures (24.8%). Hypoxemia developed in 51 patients (25.5%): 18 patients (9.0%) had subclinical hypoxemia, 29 (14.5%) had clinical hypoxemia and 4 (2.0%) met criteria for overt fat embolism. Most hypoxemic events occurred within 48 hours and fat embolism presented within 72 hours. Clinical signs accompanying hypoxemia included tachycardia, fever and transient altered sensorium in subsets of patients; petechial rash was uncommon. Urine fat globules were detected intermittently and thrombocytopenia was infrequent; neither correlated consistently with clinical hypoxemia. Femoral fractures and patients with multiple injuries demonstrated higher rates and greater severity of hypoxemia. Supportive care with supplemental oxygen sufficed for most symptomatic patients while a small proportion required ICU-level monitoring and ventilatory support. One death was attributed to respiratory complications related to fat embolism. Length of hospital stay correlated with hypoxemia severity and injuries, with cases requiring supportive care and monitoring.

Discussion

This prospective cohort confirms that clinically overt fat embolism syndrome is uncommon while subclinical hypoxemia after long-bone fractures is relatively frequent and may precede clinical deterioration. The demographic profile of predominantly young men injured in road traffic accidents mirrors regional trauma patterns and aligns with prior reports. The higher incidence and greater severity of hypoxemia observed in femoral fractures and in patients with multiple injuries supports the view that greater marrow content and increased injury burden elevate risk. Temporal clustering of events within the first 48–72 hours emphasises an early surveillance window when serial arterial blood gases and continuous pulse oximetry can detect impending respiratory compromise. Classic laboratory tests such as urine fat globules and platelet counts were inconsistently helpful and should support rather than replace clinical monitoring. Preventive emphasis should remain on early immobilization, rapid transfer and timely definitive fixation where feasible. While older surgical and military series documented frequent embolic events in battle and operative casualties [19] [20], modern series with early fixation and improved critical care report lower mortality but still show that severe cases can progress to ARDS and require ventilatory support. Limitations of this work include single-centre design, finite sample size and absence of advanced embolic detection modalities such as transesophageal echocardiography or MRI for cerebral microembolism, which may underestimate subclinical events. Despite these constraints, the data provide practical guidance for tertiary orthopaedic centres with similar casemix: heightened vigilance during the first 72 hours, routine ABG monitoring for at-risk patients and prompt supportive care when hypoxemia is detected. These measures are feasible, low-cost and can be audited prospectively to measure impact.

Conclusion

In this prospectively collected series of 200 patients with lower limb diaphyseal fractures, hypoxemia occurred in 25.5% and clinically apparent fat embolism in 2%. Hypoxemia most commonly presented within 48 hours and fat embolism within 72 hours of injury. Femoral fractures and multiple injuries were associated with higher risk. Urine fat globules and thrombocytopenia were of limited predictive value; serial arterial blood gases combined with continuous pulse oximetry and close clinical observation were more reliable for early detection. Early immobilization, prompt stabilization and rapid escalation to higher monitoring when required remain the most practical measures to reduce progression to overt fat embolism in similar tertiary-care settings. The findings support focused early surveillance protocols, strengthening of prehospital immobilization practices and training for peripheral staff to expedite referral. These baseline data can inform local protocols and provide a platform for larger confirmatory studies that evaluate prophylactic and therapeutic strategies and policy.

References

1. Saigal R, Mittal M, Kansal A, Singh Y, Kolar P, Jain S. Fat embolism syndrome. JAPI. 2008 Apr; 56.

2. Akhtar S. Fat embolism. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2009 Sep; 27(3):533–50.

3. Maitre S. Causes, clinical manifestations, and treatment of fat embolism. Virtual Mentor. 2006 Sep; 8(9):590–2.

4. Stein PD, Yaekoub AY, Matta F, Kleerekoper M. Fat embolism syndrome. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2008 Dec; 336(6):472–7.

5. Mellor A, Soni N. Fat embolism. Anaesthesia. 2001 Feb; 56(2):145–54.

6. Eriksson EA, Pellegrini DC, Vanderkolk WE, Minshall CT, Fakhry SM, Cohle SD. Incidence of pulmonary fat embolism at autopsy: an undiagnosed epidemic. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2011 Aug; 71(2):312–5.

7. Johnson MJ, Lucas GL. Fat embolism syndrome. Orthopedics. 1996; 19:41–48.

8. Scuderi CS. The present status of fat embolism. Int Surg Digest. 1934 Oct; 18(4):195–215.

9. Fenger C, Salisbury JH. Diffuse multiple capillary fat embolism in the lungs and brain is a fatal complication in common fractures. J Chicago Med Exam. 1879; 39:587–95.

10. Peltier LF. Fat embolism: a perspective. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2004 May; 422:148–53.

11. Payr E. Further contributions to the knowledge and explanation of fat-embolic death after orthopaedic surgery. Z Orthop Chir. 1900; 7:338.

12. Newbigin K, Souza CA, Torres C, Marchiori E, Gupta A, Inacio J, and Armstrong M, Peña E. Fat embolism syndrome: state-of-the-art review focused on pulmonary imaging findings. Respir Med. 2016 Apr; 113:93–100.

13. Purtscher O. Angiopathia retinae traumatica. Albrecht von Graefe’s Arch Ophthalmol. 1912; 82:347–71.

14. Peltier LF. Nail design; an important safety factor in intramedullary nailing. Surgery. 1950 Oct; 28(4):744–8.

15. Peltier LF. Fat embolism following intramedullary nailing: report of a fatality. Surgery. 1952 Oct; 32(4):719–22.

16. Tanton J. L’embolie graisseuse traumatique. J de Chir. 1914; 12:287–96.

17. Wilson JV, Salisbury CV. Fat embolism in war surgery. Br J Surg. 1944 Apr; 31(124):384–92.

18. Scully RE. Fat embolism in battle casualties: incidence, clinical significance and pathologic aspects. Am J Pathol. 1956 Jun; 32(3):379.

19. Collins JA, Gordon WC Jr, Hudson TL, Irvin RW Jr, Kelly T, Hardaway RM 3rd. Inapparent hypoxemia in casualties with wounded limbs: pulmonary fat embolism? Ann Surg. 1968 Apr; 167(4):511.

20. Cloutier CT, Lowery BD, Strickland TG, Carey LC. Fat embolism in battle casualties in hemorrhagic shock. Mil Med. 1970 May; 135(5):369–73.

| How to Cite this Article: Kota A, Pradhan C, Patil A, Puram C, Sonawane D, Shyam A, Sancheti P. Fat Embolism Syndrome in Trauma: Evaluating Long Bone Fracture‐Related Risk Factors and Patient Outcom. Journal of Medical Thesis. 2022 January-June; 08(1): 5-8. |

Institute Where Research was Conducted: Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

University Affiliation: Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS), Nashik, Maharashtra, India.

Year of Acceptance of Thesis: 2019

Full Text HTML | Full Text PDF

Ten Year Survivorship and Functional Improvement after Total Knee Replacement: A Prospective Cohort Study

Vol 8 | Issue 1 | January-June 2022 | page: 01-04 | Ravi Teja, Parag Sancheti, Kailas Patil, Sunny Gugale, Sahil Sanghavi, Yogesh Sisodia, Obaid Ul Nisar, Darshan Sonawane, Ashok Shyam

https://doi.org/10.13107/jmt.2022.v08.i01.170

Author: Ravi Teja [1], Parag Sancheti [1], Kailas Patil [1], Sunny Gugale [1], Sahil Sanghavi [1], Yogesh Sisodia [1], Obaid Ul Nisar [1], Darshan Sonawane [1], Ashok Shyam [1]

[1] Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Darshan Sonawane,

Sancheti Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation PG College, Sivaji Nagar, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Email : researchsior@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background: Osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis of the knee cause pain and disability; primary total knee replacement (TKR) is the standard surgical treatment for end-stage disease. This study reports mid-term outcomes after posterior-stabilized fixed-bearing TKR in a regional teaching hospital.

Methods: We retrospectively traced 209 patients (216 knees) who underwent primary TKR between 2005 and 2010 and assessed them between July 2016 and November 2018 (minimum eight-year follow-up). Clinical evaluation included Knee Society Score, Oxford Knee Score, SF-36 and a visual analogue scale for pain. Radiographs were reviewed for alignment and loosening. Survivorship analysis used aseptic mechanical failure and overall revision as endpoints.

Results: At follow-up, mean postoperative range of motion was 109.7° (SD 11.2°). Most patients achieved good to excellent functional scores and high satisfaction. Implant survivorship was excellent with aseptic mechanical survival of 99.5% and overall survivorship of 98.5%. Four major complications (≈1.9%) were recorded and ten patients were lost to follow-up.

Conclusion: Posterior-stabilized fixed-bearing TKR provided durable mid-term pain relief, meaningful functional restoration and high implant survival in this cohort. Careful patient selection, appropriate sizing and meticulous surgical technique likely contributed to favourable outcomes.

Keywords: Total knee replacement, Posterior-stabilized, Survivorship, Oxford Knee Score, Long-term outcomes, Single-centre experience India.

Introduction:

Knee osteoarthritis is a progressive disorder that damages cartilage, modifies subchondral bone and produces pain, stiffness and limited function that impair everyday life. When nonoperative measures fail, total knee replacement (TKR) delivers reliable pain relief and restores mobility for most patients, and it is now a standard solution for end-stage disease. Improvements in implant design, surface processing and surgical technique over recent decades have increased durability and functional outcomes, with many implants showing favourable ten-year survivorship in large series and registries [1–4].

Surgical technique — particularly accurate component alignment and careful soft-tissue balancing — remains decisive for good results, since malalignment or imbalance predisposes to asymmetric wear, instability and early failure [5–7 ]. Patient factors such as age, body composition and bone quality influence both disease progression and postoperative recovery, and therefore must guide implant choice and perioperative planning.[8–10 ] Regional anthropometric differences in knee geometry have been described and can affect component fit; local sizing considerations are important to avoid mismatch and suboptimal biomechanics [11–13].

Complications such as periprosthetic infection, fracture and persistent pain continue to challenge surgeons and may lead to revision procedures, reinforcing the need for meticulous surgical technique, appropriate perioperative protocols and long-term follow-up [14–16]. Despite abundant international literature, outcome data from regional centers are valuable because activity patterns, expectations and anatomy may differ. This study presents mid-term clinical, functional and radiological outcomes and survivorship for patients who underwent primary posterior-stabilized fixed-bearing TKR at a single teaching hospital.

Aims and Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate mid-term clinical and functional outcomes of primary posterior-stabilized fixed-bearing total knee replacement performed at a single teaching hospital. Primary objectives were to measure pain relief, functional recovery and implant survivorship using aseptic mechanical failure and overall revision as endpoints. Secondary objectives included documenting complication rates, comparing outcomes across age groups, and quantifying range of motion alongside validated scores (Knee Society Score, Oxford Knee Score and SF-36). Findings were intended to inform local surgical practice and identify priorities for future research and registry work.

Review of Literature

Osteoarthritis is now recognized as a disease of the whole joint, where cartilage degeneration, subchondral bone change and synovial inflammation interact to produce symptoms and structural progression [17, 18]. Understanding inflammatory mediators and matrix degradation pathways has improved our approach to symptom control and perioperative optimization [19]. Patient phenotype including obesity, bone mass and muscle composition — affects disease risk and post-replacement recovery, which underlines the need for individualized planning [10, 20].

Condylar TKR evolved through iterative refinements aimed at restoring near-physiologic kinematics while limiting polyethylene wear. Registry data and projection studies show rising demand for both primary and revision arthroplasty as populations age, but also demonstrate satisfactory ten-year outcomes for many modern systems when surgical technique and implant selection are appropriate [1, 3, 4]. Design changes have focused on improved conformity, wear resistance and options for constraint to suit ligament status [5].